Focus: Energy Transition at What Cost

Author: Nicolas Sioné

Welcome to this new edition of CIGP WM Focus which discusses the ever growing importance of safe havens by taping into the notions of

- Future uncertainty

- Identifying adverse events

- Safe haven vehicles

- The status of treasuries

- Adapting investment strategies

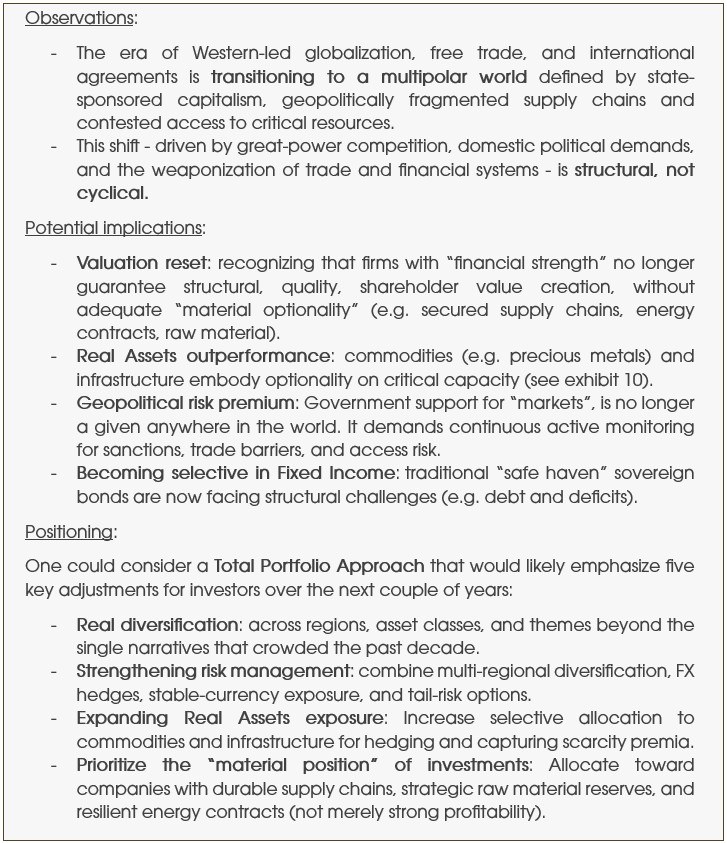

After several decades being dominated by post-WW2 Western-led institutions (e.g. IMF, World Bank, WTO, NATO), which promoted a specific model of globalization through neoliberal policies (e.g. free markets, privatization, deregulation), the world is now entering a multipolar era defined by greater state intervention and regional power balances. The old paradigm of a unipolar economic and cultural hegemony, characterized by free trade, capital mobility, and the near-universal embrace of Western market models, is being challenged in our view. In its place rises an environment of state-sponsored capitalism, where nations prioritize strategic industries and security over financial efficiency, reshaping global trade patterns and financial systems. This transition is in our view structural rather than cyclical: it stems from geopolitical shifts, policy choices in major economies, and even changing societal attitudes. Crucially, it is not a zero-sum regression and presents new opportunities alongside challenges. Investors need to adjust to these new realities by diversifying beyond the market themes that have dominated the last decade, across different regions and asset classes. Below, we dissect this transformation in five parts: (1) the end of the neoliberal era, (2) the emergence of state-driven capitalism, (3) the redrawing flows of goods and money, (4) changes in cultural hegemony, and lastly (5) the implications for investments in a multipolar world.

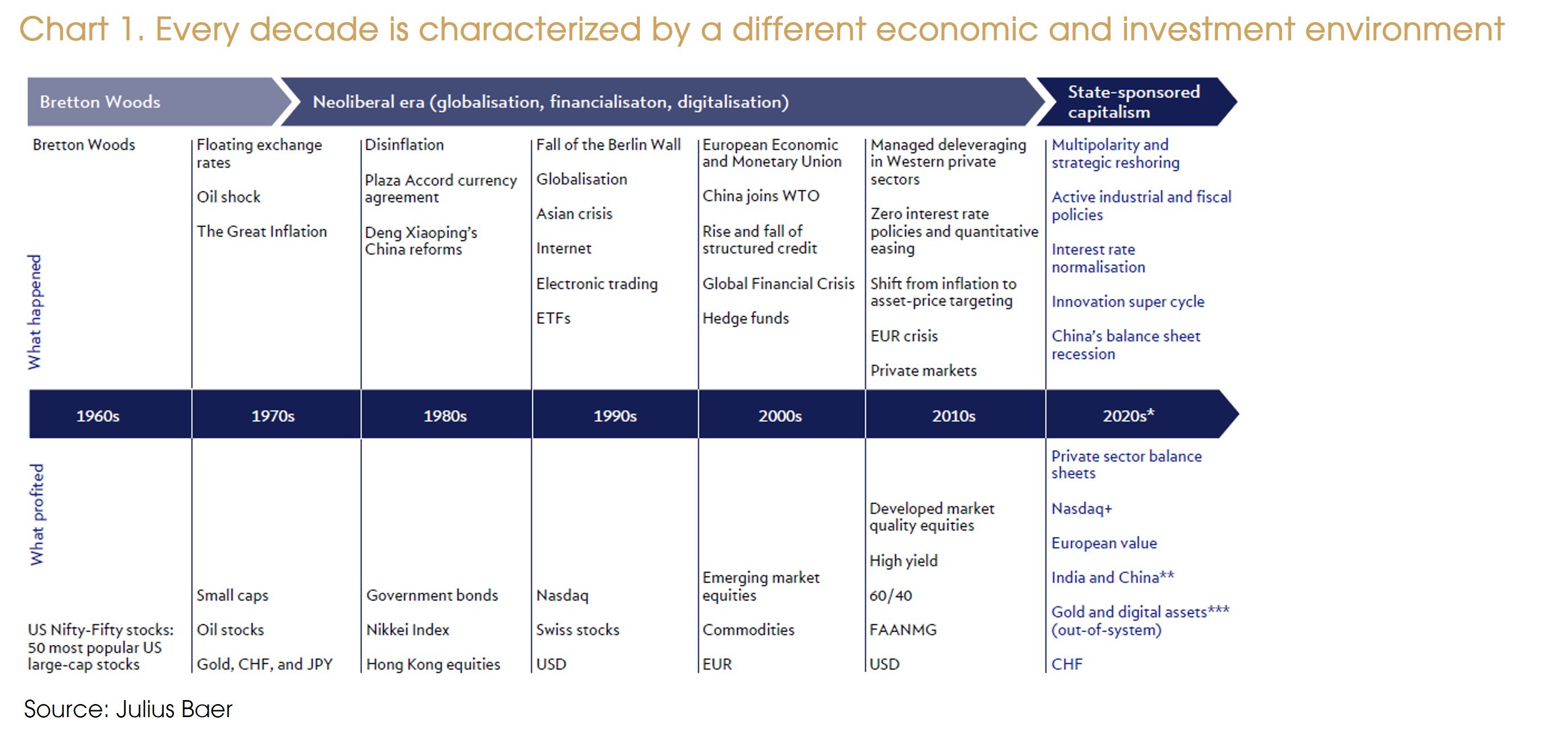

The post-Cold War neoliberal era (i.e. roughly the 1990s through 2010s) was defined by ever-deeper globalization, market deregulation, and U.S. economic primacy. Western-led institutions and norms (e.g. the “Washington Consensus”) promoted free markets, privatization, and trade liberalization across the world. This era delivered a long upswing in global growth and a great moderation of inflation, while extending complex supply chains worldwide. One of the most notorious developments of globalization is the rise of new economic powers (i.e. BRICS) which, through their growing influence, have reshaped global institutions once dominated by Western dogma. In our view, this is counterintuitively pushing some Western powers to use alternative policies, in their quest to protect the founding principles of the institutions mentioned above.

However, the conditions that underpinned this “unipolar moment” have steadily eroded in recent years. The 2008 Global Financial Crisis exposed excesses in the Western financial model, and the 2010-2020s saw populist backlashes against inequality in many advanced economies. More decisively, geopolitical events in the late 2010s marked the break. The U.S.–China trade war and especially the 2018 U.S. semiconductor embargo on China signaled the end of automatic cooperation in global trade. From that year onwards, great powers began securitizing trade and technology. Once taken for granted, the Western financial markets neutrality and openness have been called into question, as illustrated by the most striking example in 2022, when a coalition of states including all G7 economies froze approximately US$300 billion in Russian state assets in response to the Ukraine conflict, prompting many countries into rethinking dollar reliance.

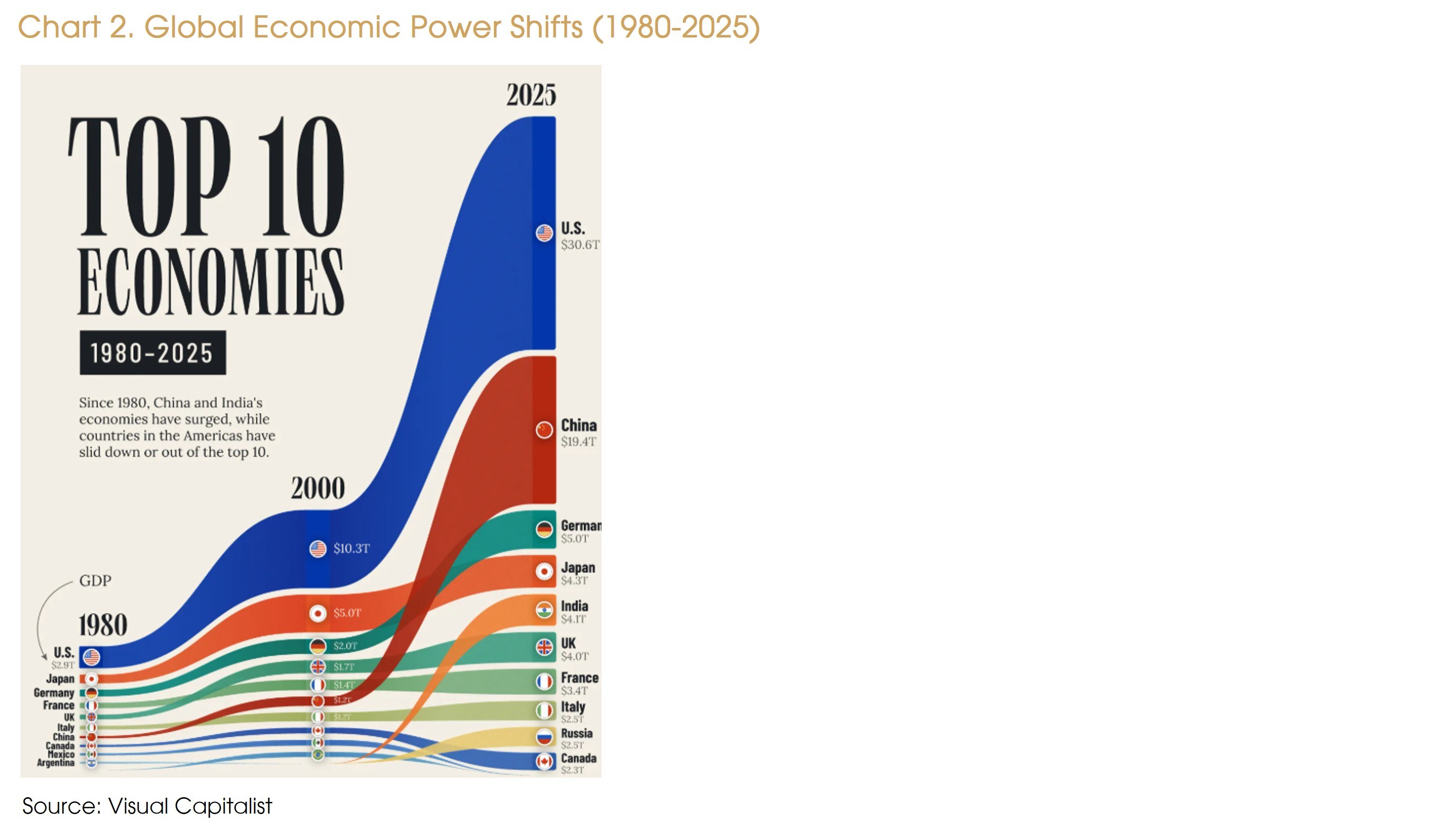

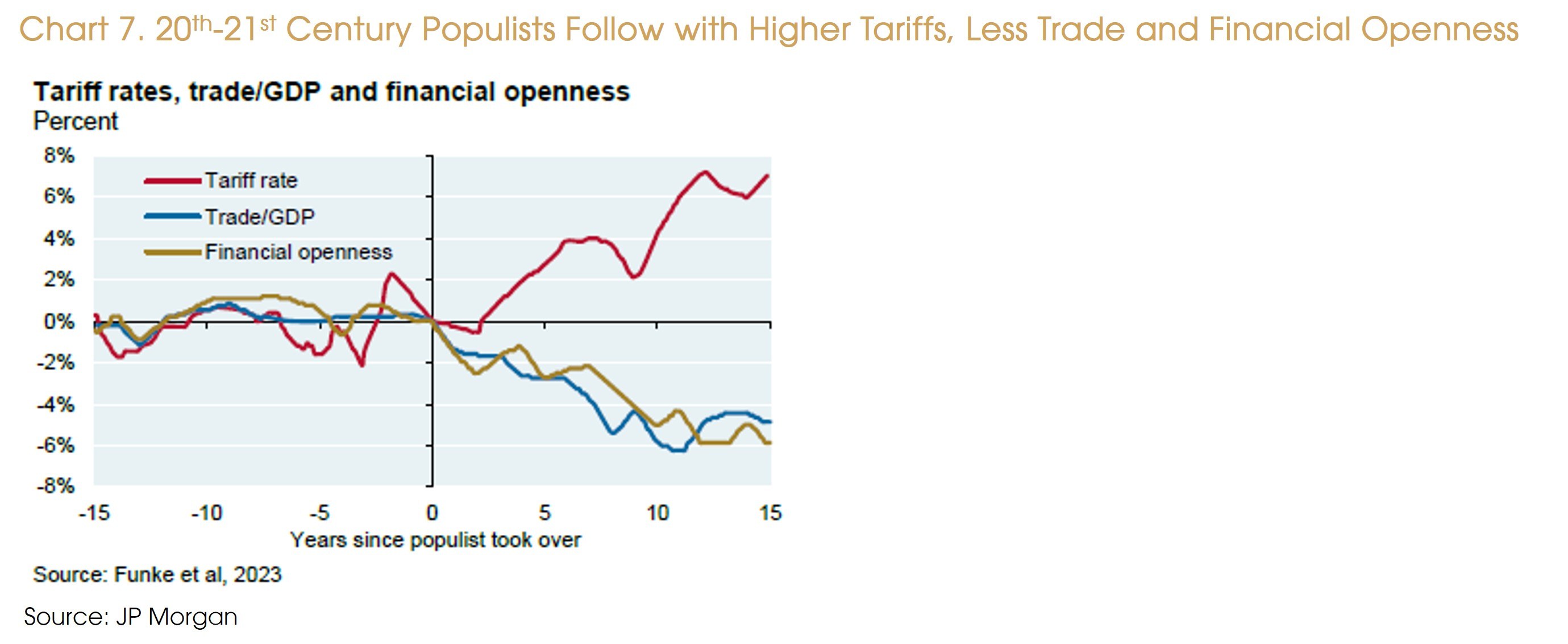

Last, global trade is no longer the engine of economic growth that it once was, and new trade barriers have been erected (e.g. U.S. average tariff rates are forecast to hit the highest levels since 1910s).

Importantly, the end of the neoliberal era has been accelerated by policy choices and domestic shifts within the West itself. The United States and European Union have both experienced surges in economic nationalism and interventionism. Protracted low growth, loss of international relevance and rising inequality created political demand for change. As a result, the 2020s have featured a break from the “laissez-faire orthodoxy”: protective supply-side policies are being put in place, reindustrialization and critical materials are now a national priority (e.g. as seen with the Defense sector) and cross-border trade deals are becoming more complex. In the U.S., this break became especially visible under the Trump first administration’s “America First” approach (2017–2021) and has continued in key areas under the current leadership. The overall effect has seen greater fragmentation of the global system, a shift away from the seamless global markets of neoliberal globalization toward a heterogeneous patchwork of spheres, where fragile and unilateral agreements will prevail over universalism (as described in the last 2025-US National-Security-Strategy.pdf).

Over the last years, governments have been taking a much more active role in their economies. This represents a pivot from the neoliberal ideology that “the market knows best” (i.e. a focus on the demand-side of the economic balance) to a model often described as state-sponsored capitalism or “economic statecraft” (i.e. supply-side economics). Major powers are now consciously trading some economic efficiency in return for greater control, security, and resilience. They are pursuing industrial policies, subsidizing domestic champions, and leveraging the state’s balance sheet to achieve strategic aims. Several forces are driving this.

Geopolitically, great-power rivalry has made some nations anxious about relying on foreign suppliers for critical goods. The supply chain disruptions during the pandemic (e.g. semiconductor shortages) and wartime sanctions (e.g. on Russian energy) underscored the vulnerability of just-in-time, globally dispersed production. In response, governments now openly talk about “sovereignty” in supply chains. The recent U.S. military operation in Venezuela illustrates how state directed power may increasingly become an instrument for resource exploitation/securitization.

At the same time, there is a “domestic legitimacy deficit” in many societies, putting pressure on leaders to deliver tangible economic benefits. In democracies, disillusionment with stagnant real wages and unemployment has fueled populist movements and political polarization that demand a stronger government hand in the economy (e.g. promises to rebuild factories, favor local workers, lower the real borrowing costs in the economy). In autocracies, leaders justify their rule by pointing to developmental successes and thus feel compelled to steer resources into visible national achievements.

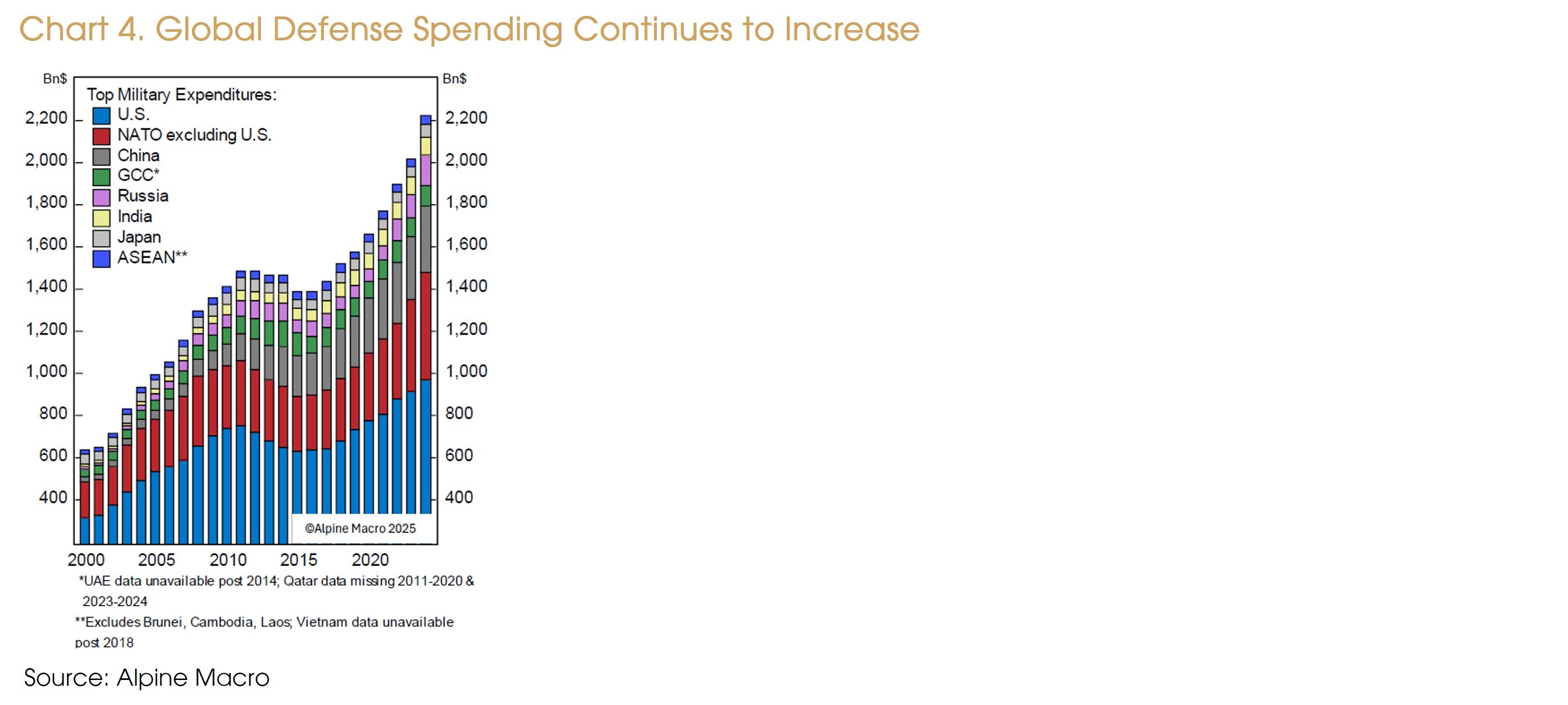

This new era of state-sponsored capitalism has far-reaching implications. One immediate effect is a boom in capital spending on strategically important areas. We are seeing multi-year investment agreement in areas such as Energy, Defense and Semiconductors. Most (if not all) propelled by government initiatives.

Another consequence is higher inflationary pressures on input prices compared to the pre-2020 period. State interventions (e.g. tariffs) tend to raise costs. Redundant supply chains and friend-shoring are by definition less cost-efficient than pure globalization, as duplicating strategic facilities adds inefficiency - a structural cost headwind, not merely cyclical price pressures. Over time, we think more structurally embedded price pressures may be part of this new multipolar, state-driven world, in stark contrast to the disinflationary excess capacity of the 1990s–2000s. Central banks will have to balance between accommodating these fiscal/industrial pushes with their price stability mandates (i.e. where rising costs to flow into end-customer prices), a delicate task in our view.

One of the clearest manifestations of the transition to a multipolar world today is in global trade and finance. After a long era in which trade was steadily liberalized and the world’s supply chains and means of payments (backed by the hegemon currency - i.e. the U.S. Dollar) converged, we are now seeing trade realignment along geopolitical lines and a rethinking of trade settlements for cross-border payments. Several key trends stand out:

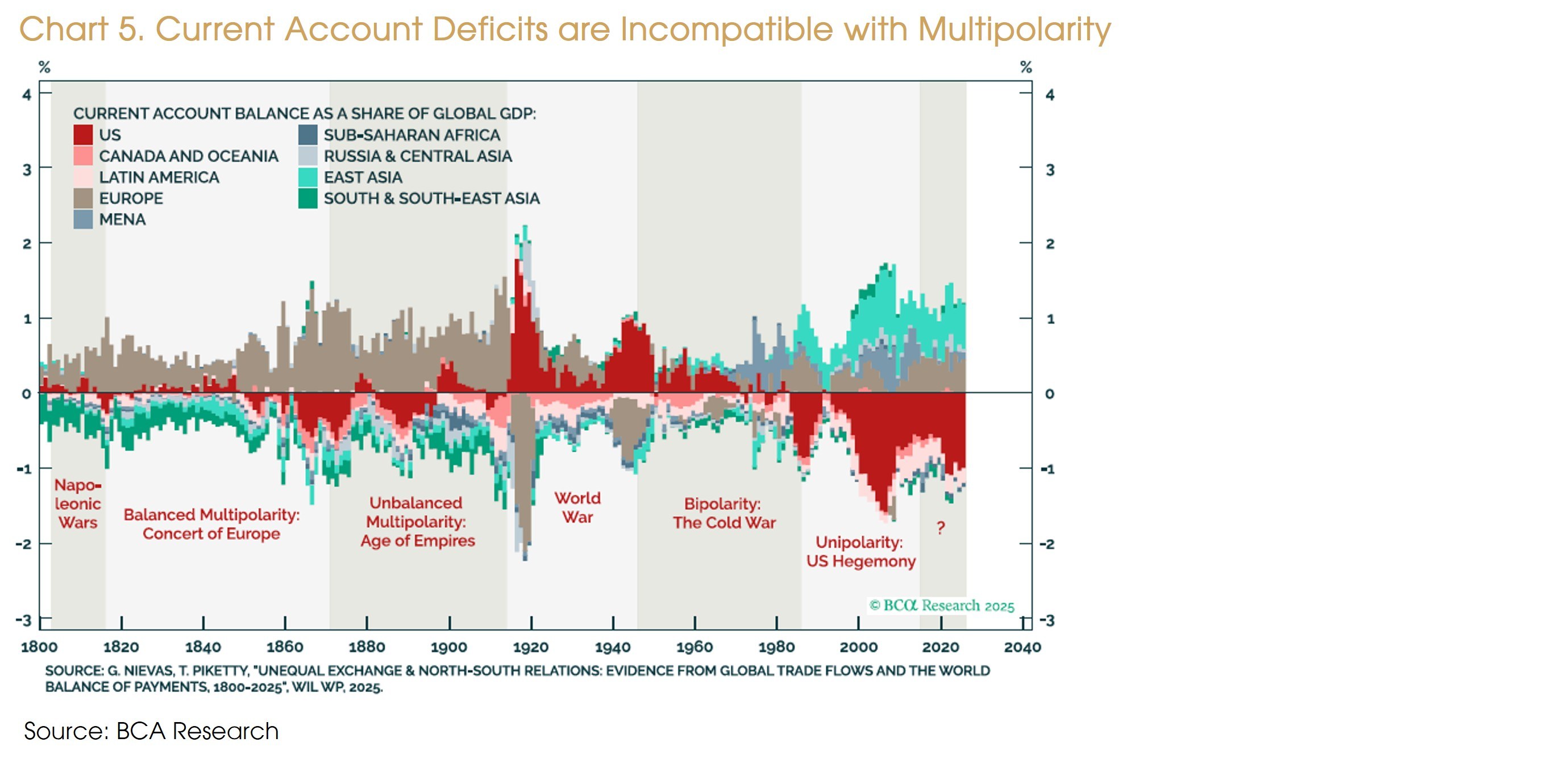

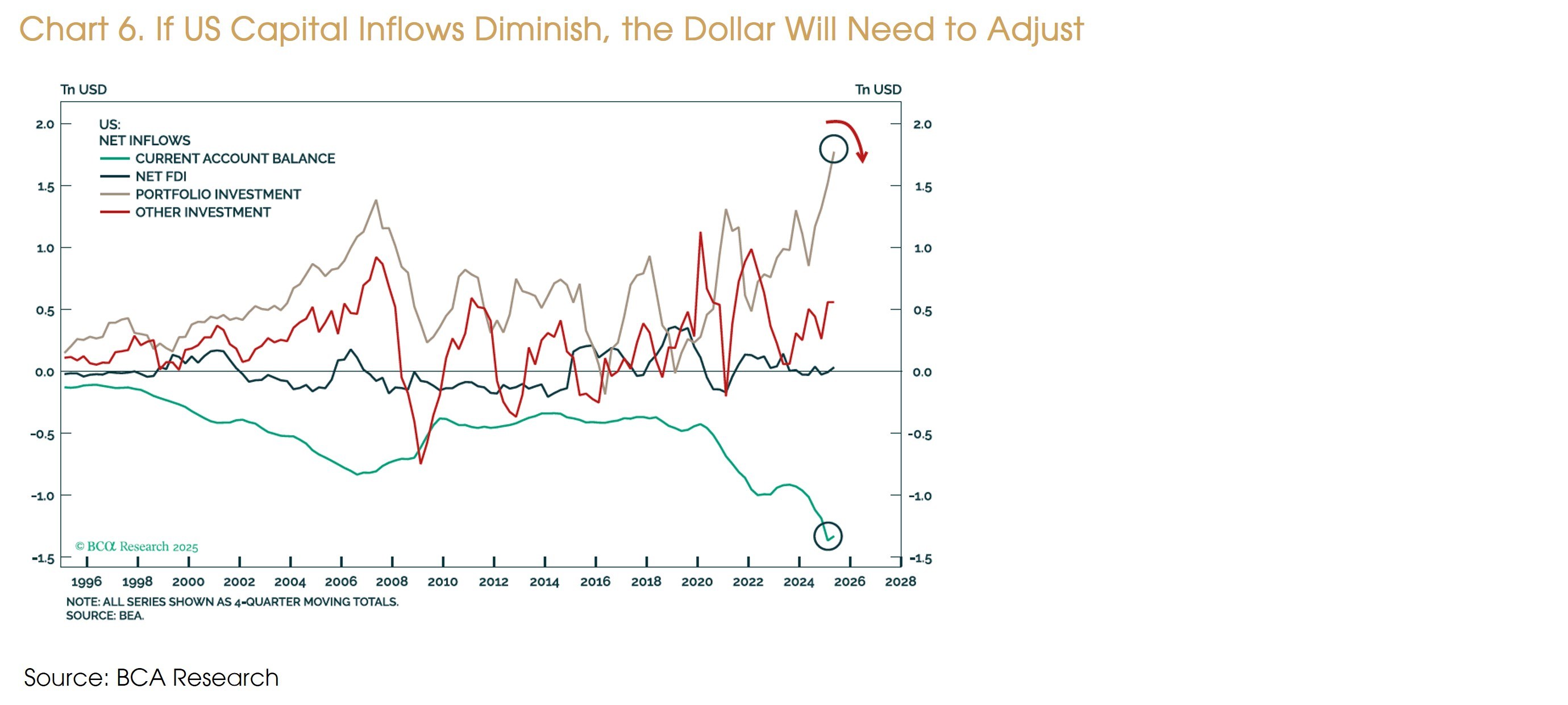

- Reroute of global trade flows: Overall, global trade volumes have recovered post-pandemic, but “who trades with whom” is changing. Rather than a single integrated global trading system (i.e. with universally respected trade agreements and settlement systems), we are now moving toward a world of overlapping trade blocs. To that matter, the structure of global current accounts (i.e. who run trade surpluses and deficits) is likely to adjust in a multipolar regime. During the previous unipolar era, the U.S. ran persistently large current account deficits (importing far more than it exported) and these were willingly financed by surplus countries (e.g. Japan, China, EU) in a stable geopolitical context. The bottom line to us is that geopolitics now dictates trade flows to an extent not seen in decades.

- De-Dollarization and new financial infrastructure: Perhaps one of the most discussed elements of multipolarity is the “de-dollarization” trend. This entails a gradual reduction in the global economy’s reliance on the U.S. dollar as a: 1) mean for international trade settlement and 2) reserve asset (i.e. to store trade surpluses). Indeed, some countries are now seeking to avoid dependency on a U.S.-centric system that could subject them to sanctions or financial conflict (i.e. a concern sharpened by the freezing of Russia’s dollar assets in 2022). As previously stated, global capital flows are shifting as surplus economies prioritize domestic investment, consumption and alternative partnerships (e.g. Belt and Road Initiative within the “South-South cooperation”). This move is in turn accelerating the use of alternative currencies, the growth of new payment and settlement systems, and increased central bank gold accumulation. Notably, China is actively promoting RMB-based trade settlement through bilateral swap lines and its Cross-Border Interbank Payment System (CIPS) as an alternative to the dollar-centric payment infrastructures. This is already visible in the commodities’ space, which is the backbone of global settlement (e.g. the petrodollar system tied the dollar to oil trade). In a multipolar context, we might see more commodities priced in non-dollar terms or exchanged in barter-like arrangements (e.g. India has bought Russian oil at discounts using RMB). In parallel, countries are stockpiling strategic commodities (e.g. gold, oil) as a: 1) hedge against trade disruption and 2) to promote confidence in the country´s reserve assets.

- From financial claims to material ledgers: State-sponsored capitalism presents a paradox: while governments can create unlimited financial capital through central bank operations, they face immutable physical constraints. The 2025 Novelis aluminum facility fire, which idled Ford's assembly lines despite the automaker's robust credit and liquidity metrics, exemplifies this decoupling (i.e. binding constraints now lie in physical, not financial capacity). In our view, a multipolar financial infrastructure may require not replacement of the dollar with a rival reserve asset, but movement toward physical-asset-backed allocative systems where claims on resources are negotiated bilaterally or within regional blocks rather than mediated through a single settlement currency. Gold accumulation by central banks and the rise of commodity-based trade settlement mechanisms reflect this adaptation in our view.

Lastly, we would highlight that in our view the fragmentation of global trade routes does not mean that global trade is over. However, we believe that global trade and consumption will become less important in the years to come for global economic growth. In essence, we expect investment (e.g. capital formation) to play a more significant role in global economic development going forward.

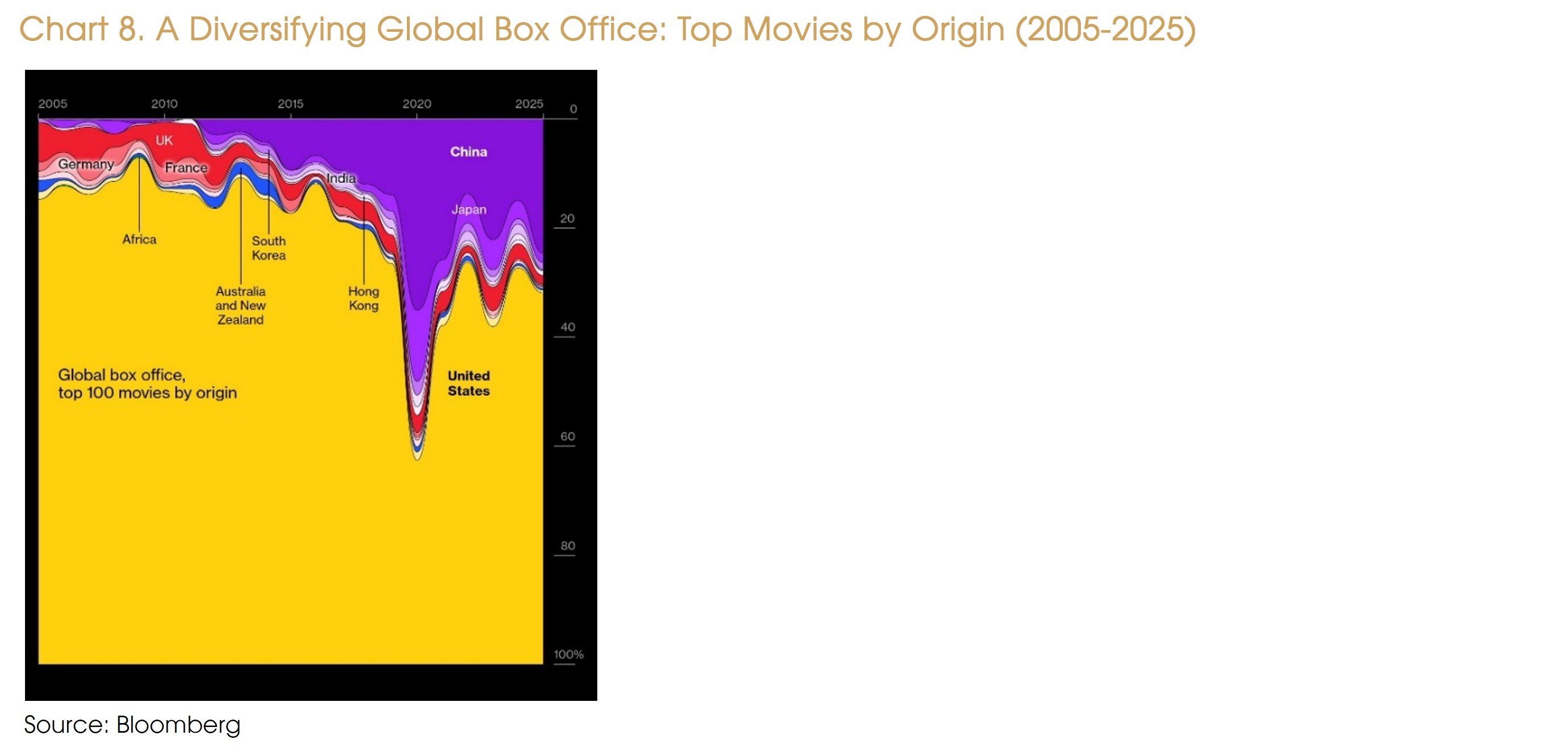

The rise of a multipolar world is also reshaping global cultural and ideological influence, marking a shift from Western dominance toward a more pluralistic landscape. While Western soft power once reigned through media, education, and liberal democratic ideals, its monopoly is eroding as non-Western cultures and governance models gain traction. South Korea’s K-pop, India’s Bollywood, and Chinese platforms like TikTok exemplify the global appeal of diverse cultural exports. Meanwhile China, Russia, and Gulf states actively invest in media, education, and sports to project their own narratives. Furthermore, global governance forums (e.g. G20, World Bank, United Nations) now reflect competing values, with middle powers asserting regional priorities and contesting Western norms. Localization is also rising, as nations promote indigenous languages, cultural pride, and region-specific content, leading to a de-centering of global influence.

Though Western culture remains influential, the trend points to a more competitive and fragmented soft-power environment. For investors, cultural shifts are harder to quantify than trade or GDP, but they influence market sentiment and consumer behavior in the long run. This demands cultural agility and localized strategies, as consumer preferences and societal values become increasingly diverse across regions. We think domestic brands and IP tailwinds are an area of investment opportunity.

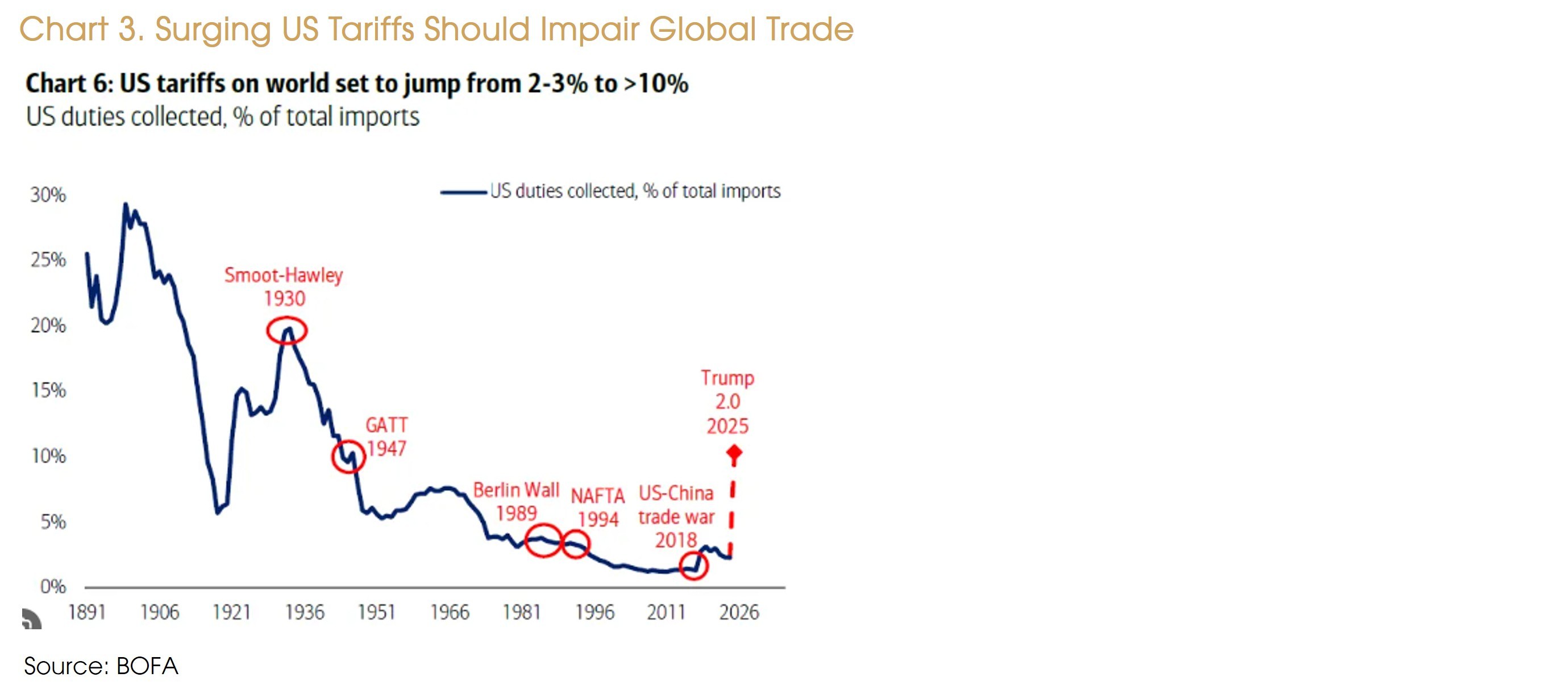

The shift to a multipolar, state-driven, and fragmenting global landscape will have profound implications for investors. The strategies that outperformed during the era of Western-led hyper-globalization may no longer be sure winners (as seen in Exhibit 1.). At the same time, new opportunities are arising in asset classes and regions that stand to benefit from the reordering. Overall, we think that in a multipolar world, investors must dynamically evolve with the changing economic environment by adopting a Total Portfolio Approach (TPA) that emphasizes diversification across a broad range of traditional and alternative assets with attractive risk/reward prospects. Moreover, we would emphasize that big shifts like those detailed in this note can take time and therefore our views are to be implemented gradually and over time. Here we outline key investment implications and potential adjustments:

- The valuation reset from neoclassical “demand” economics to “supply-constrained” economics: The transition to multipolarity necessitates a fundamental reset in how investors value returns. For forty years, capital markets operated under an implicit assumption: financial capital and physical capacity move together (i.e. abundant liquidity reliably converts into productive output). This linkage, whereby “physical/material reality” is subordinated to “financial markets” may be coming to an end in our view (e.g. The U.S. Official Mint recent temporarily suspension of physical silver deliveries due to price volatility is a good example of this). In an environment of state control, supply-chain fragmentation and contested access to critical materials, outcomes are decided not by market coordination, but by who secures materials, sustains throughput and withstands time. This reordering demands investors distinguish between firms with a strong “financial” position (e.g. strong balance sheets, profitability, growth) and those with a strong “physical/material” position, which could ultimately help them overcome physical bottlenecks (e.g. secure supply chains, strategic raw material reserves, resilient energy contracts). A firm may remain solvent indefinitely while remaining illiquid in “physical terms” (i.e. unable to convert cash into the specific inputs required for production). In a multipolar world where material access is increasingly contested, financial health is a necessary but insufficient condition for value creation. Going forward, even traditionally insulated firms like software companies should increasingly reflect material position durability over balance sheet strength in valuations; a risk we believe markets currently underprice.

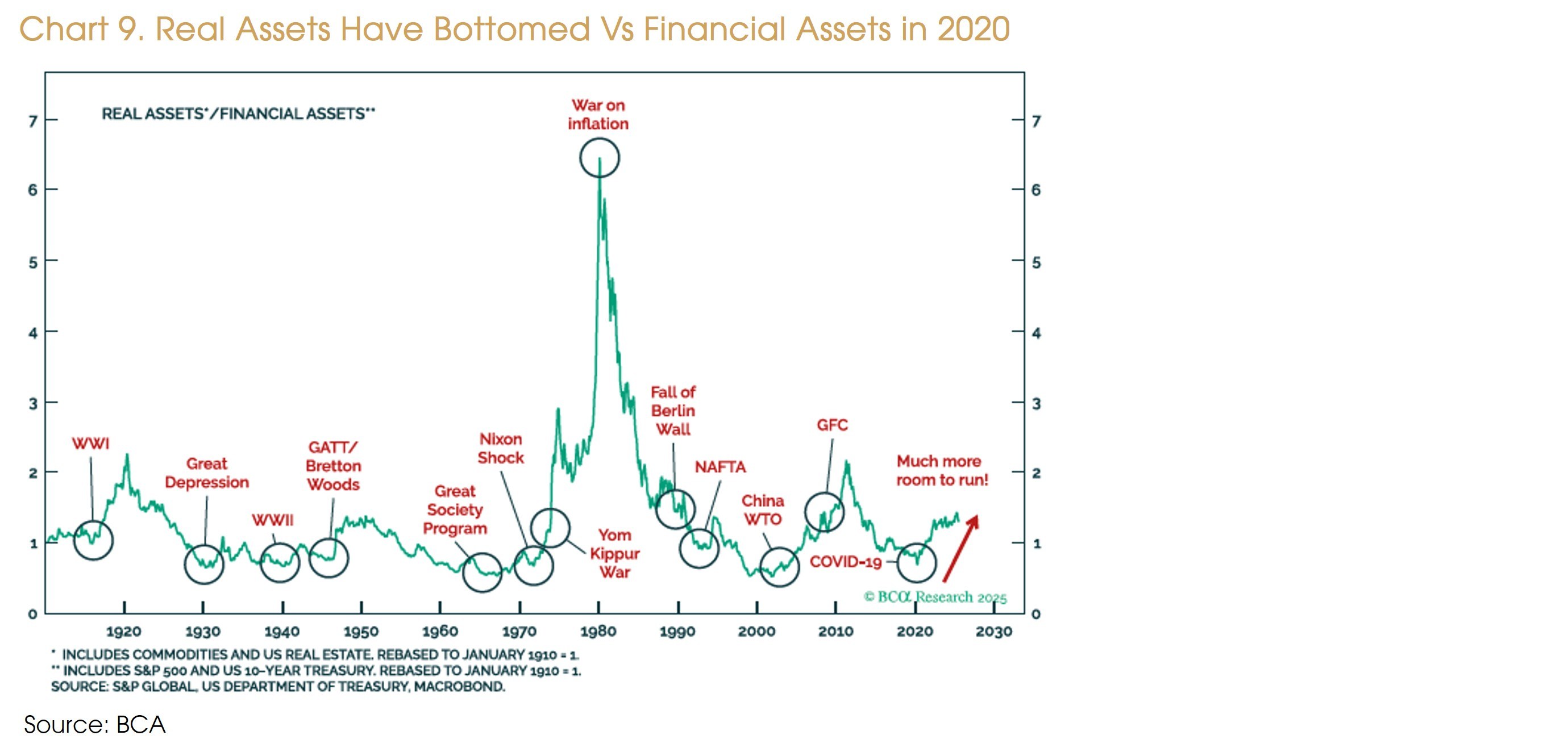

- Expand Real Asset allocation: beyond traditional inflation hedging, real assets (e.g. commodities, precious metals and infrastructure) that combine scarcity with resilience, now embody optionality on critical capacity. Many industrial metals are critical to energy transition and rearmament (e.g. as depicted by the US Federal Register: final 2025 List of Critical Minerals), while gold is increasingly viewed as a monetary hedge amid de-dollarization and central bank accumulation. Furthermore, in a multipolar world, the “physical conversion rate” (i.e. how rapidly a firm converts cash into finished goods, under constrained conditions – such as a supply chain bottlenecks) becomes a paramount valuation metric. This shift elevates assets with high durability through the cycles (e.g. mines that operate below nameplate capacity, smelters with reliable energy contracts, manufacturers with geographically diversified supply networks). Conversely, firms dependent on just-in-time logistics or single-sourced critical inputs may face valuation compression as their conversion rates decline.

- Strengthen Risk Management: In a less predictable and more volatile geopolitical environment, investors should enhance their risk management framework. 1) In a more complex, fragmented multipolar world, we believe that there should be a broadening of returns across different investment themes compared to the last ten years. A multi-regional portfolio helps mitigate political and policy risks tied to any single hegemon. One way to mitigate the risk is through FX hedges. 2) We recommend maintaining exposure to traditional safe havens (see our previous whitepaper: In Focus: The Growing Importance of Safe Havens - CIGP), short-term/liquid assets, and stable currencies (e.g. CHF). 3) Last, we also advise considering non-traditional hedges, such as tail-risk option strategies. In our view, a resilient portfolio for the years to come will balance global opportunities with robust downside protection.

- Refined Fixed Income strategy: The era of structurally falling yields and disinflation is likely over in our view. Most developed-market sovereign bonds face headwinds from rising debt, persistent inflation, and fiscal expansion. Instead, investors should focus on high real-yielding local-currency bonds in selected markets with sound macro fundamentals and appreciating currencies. Additionally, we recommend investors continue seeking fixed-income instruments which offer low correlation to the global macro and potential resilience in volatile markets.

- Integrating Government Policy in the investment process: government intervention is no longer a tailwind to assume and hold. In a multipolar, fragmented world, state involvement creates both acute opportunities and risks that demand continuous monitoring. For instance, a sector may be subsidized and strategically backed in one jurisdiction while facing restrictions in another (e.g. Chinese EV battery manufacturers gain from state support while facing trade barriers in some Western states). Consequently, we think that investors must embed geopolitical bifurcation into their research process, not as a static overlay but as an ongoing discipline. Concretely speaking, this means: 1) mapping the sectors that align with each major power bloc's strategic priorities; 2) stress-testing holdings for sanctions, supply-chain restrictions, or asset seizure risk; and 3) recognizing that "picking the winners" from government support requires active monitoring, not passive buy-and-hold. The multipolar shift amplifies the importance of this work, as capital is increasingly allocated rather than auctioned, and proximity to government favor becomes a material valuation factor, but only if reassessed regularly.

[JM1]Which currency is stable? CHF?

[GM2]Yep, that’s an example

[AV3]Hehe, what else is stable? Honest question.

[GM4]Would definitely have to look more in detail (hence why I don’t want to put more examples in the paper) - but I guess countries with very independent CB, low/stable debt/GDP ratios, good government budget balances and limited political risk … Singapore? Norway? UAE? Hong Kong?

[AV5]Is this something we are doing?

[GM6]No(t yet?)

[GM7]@Jess Cheung any views?

[AS8]To a degree we are, via Sentosa and Primas. Doing it ourselves would be too complicated.

[AV9]Haha! You are right. Perhaps I should rephrase my question to is this really our view?

I may be wrong but I feel Sentosa and Primas are more of our broader hedge fund thesis (we like the manager, return profile, strategy works with an underlying of those bonds, etc.) rather than we were focusing on local currency bonds and then we found Sentosa/Primas. Do I make sense?

[JC10]Yay Miggy. I think we invest in Sentosa, and Primas is more of the manager and strategy that we like. Primas doesn’t really do any local‑currency bonds, but we are also exploring other EM funds (focus more on hard currency side). Since I joined, we’ve looked into different EM funds, probably more than five. I believe I’ve spoken to at least five different EM fund managers. I guess we lost a bit of interest later on when the DM bonds delivered more 5% return, very attractive risk reward and also the market started to get volatile and we wanted to avoid it, since EMD can be more volatile and vulnerable.

But I do think we’ve always wanted to explore this area, especially for diversification benefits. But the idea of high real‑yielding local‑currency bonds and appreciating currencies, it almost sounds too good to be true (I remember that Indian local bonds’ outlook from Alpine Macro is in this forecast)? Anyways, it’s very hard to estimate the currency impact, there’s no crystal ball. But I do think EMD is something we are missing and we’ve been making very slow progress on this.

[AV11]I think that’s clear --> perhaps we should modify this given that it might be “too good to be true”. Now, how? Not very sure; maybe a simple way is list a few examples of “high real-yielding local-currency bonds”? What country has low inflation, low fiscal debt issue, strong currency, attractive yields, etc.?

[GM12]I don’t mind adding more granularity if that is what the people of RWG want. In which case I would suggest the following examples: Poland, Mexico. India

@Jess Cheung @Andrew Sassoon

[AS13]We want to generate a discussion so would not add more granularity. We do not have the perfect answer and solution but we are looking. As Jess mentioned, our attention was elsewhere and this is a good time to look again.

[14]Anyways, i definitely think we should have a fund focus this market, even we are not investing now, but it will be there and ready to invest when we want to. Also curious and want to ask PMs, if you get a lot of interest or questions about the EM space?

[YW15]RMB bonds?

[GM16]I think it’s a good example. Hopefully the others @Jess Cheung @Andrew Sassoon think that too

[AV17]+1, RMB bonds? Blackrock China Bond fund? I could have sworn @Jess Cheung is not in favor?

[18]Miggy knows me well!! Not in favor! NO RMB Bonds! Extremely low RMB bond yield, poor fundamentals for quite a lot of companies, only catalyst is the FX and maybe more rate cuts? but overall im not in favor! I think I would rather hold other EM bonds, maybe INR bonds.

[AS19]I would remove RMB bonds but keep the same premise. We are looking and sourcing is not easy. Sentosa is doing a good job and we have had many inquiries but yields have been too low. Now with falling yields in the US, interest might come back.

[AV20]A comment I’ve had in the past, I feel this is an obvious one… Perhaps we should reframe this as incorporating government/national strategy into our investment process with defense or infrastructure as part of our thesis?

[GM21]I don’t get it?

[AV22]I struggle to express it, but somehow I think there’s a clear difference between this NEW “multipolar world” and “government intervention” which is NOT NEW. And I don’t want to conflate the two, where this bullet point feels more like invest where the government supports is a bit stating the obvious? Were we doing the opposite and investing in not-aligned sectors? I don’t know if what I mean makes sense...

Also, I am curious if it is consensus that we PRIORITIZE government intervention-related businesses?

[AV23]Maybe what I mean is having this section here in a multipolar world paper seems to imply multipolar world is why we should invest in aligned sectors, when you should invest in aligned sectors regardless of the multipolarity or unipolarity of the world. Investing with government support is just something that makes sense independent of the hegemons.

If that makes sense, I suggest to reframe this point instead of “target aligned equity sectors” (stating the obvious) and more something like along the lines of government intervention is increasingly important for our research process - or something like this?

[AS24]Either works for (and no, nothing is obvious and should not be assumes). If reframed, I would try to emphasis that it is not only for opportunities but for risks too (if you are in the West, be cautious of investing in defense or chips in China due to potential impact of inclusion in restricted lists). In other words, went govts are involved, do not take a buy and hold approach.

[GM25]Ok, let me know if the new paragraph works

[AV26]Works for me Guillermo AI - I like it and Andrew’s suggestion is good!

Disclaimer

This document is issued by Compagnie d’Investissements et de Gestion Privée Group (“CIGP”), solely for information purposes and for the recipient’s sole use and shall not be further transmitted to third parties. You have been provided with this document in your capacity as Professional Investor(s) as defined in Part 1 of Schedule 1 to the Securities and Futures Ordinance (Cap. 571). If you do not meet the Professional Investor criteria, please disregard this document.

CIGP does not assume responsibility for, nor make any representation or warranty (express or implied) with respect to the accuracy or the completeness of the information contained in or omissions from this document. None of CIGP and their affiliates or any of their directors, officers, employees, advisors, or representatives shall have any liability whatsoever (for negligence or misrepresentation or in tort or under contract or otherwise) for any loss howsoever arising from any use of information presented in this document or otherwise arising in connection with this document. This document may not be reproduced either in whole or in part, without the written permission of CIGP. Past performance is not a guarantee of future results. There can be no assurance that forecasts will be achieved. Economic or financial forecasts are inherently limited and should not be relied on as indicators of future investment performance.

This document is not a prospectus and the information contained herein should not be construed as an offer or an invitation to enter into any type of financial transaction, nor an act of distribution, a solicitation or an offer to sell or buy any investment product in any jurisdiction in which such distribution, offer or solicitation may not be lawfully made. Certain services and products are subject to legal restrictions and cannot be offered worldwide on an unrestricted basis and/or may not be eligible for sale to all investors. Unless cited to a third-party source, the information in this document is based on observations of CIGP. The information provided is based on numerous assumptions. Different assumptions could result in materially different results. Before acting on any information you should consider the appropriateness of the information having regard to your particular investment objectives, financial situation or needs, any relevant offer document and in particular, you should seek independent financial advice. All securities and financial product or instrument transactions involve risks, which include (among others) the risk of adverse or unanticipated market, financial or political developments and, in international transactions, currency risk. The contents of this report have not been and will not be approved by any securities or investment authority in Hong Kong or elsewhere.

CIGP acts as an agent when recommending or distributing investment products. The product issuer is not an affiliate of CIGP. CIGP is an independent intermediary, because: (i) we do not receive fees, commissions, or any other monetary benefits, provided by any party in relation to our distribution of any investment product to you; and (ii) we do not have any close links or other legal or economic relationships with product issuers, or receive any non-monetary benefits from any party, which are likely to impair our independence to favour any particular investment product, any class of investment products or any product issuer. Neither us nor our group related companies shall benefit from product origination or distribution from the issuers or providers, whether in monetary or non-monetary terms. We do not provide any discount of fees and charges.