CIO Viewpoint: How to take Opportunities in this Commodities Upward Cycle

Commodities are among the best-performing asset classes this year. We expect the commodities upward cycle to continue in the near to medium term. Metals may benefit more from the cycle and also have stronger tailwinds in the long run given the “green transition”. To take the opportunity of the upward cycle, commodities-related equities can be an option.

Different Supply-Demand Profiles Among Commodities

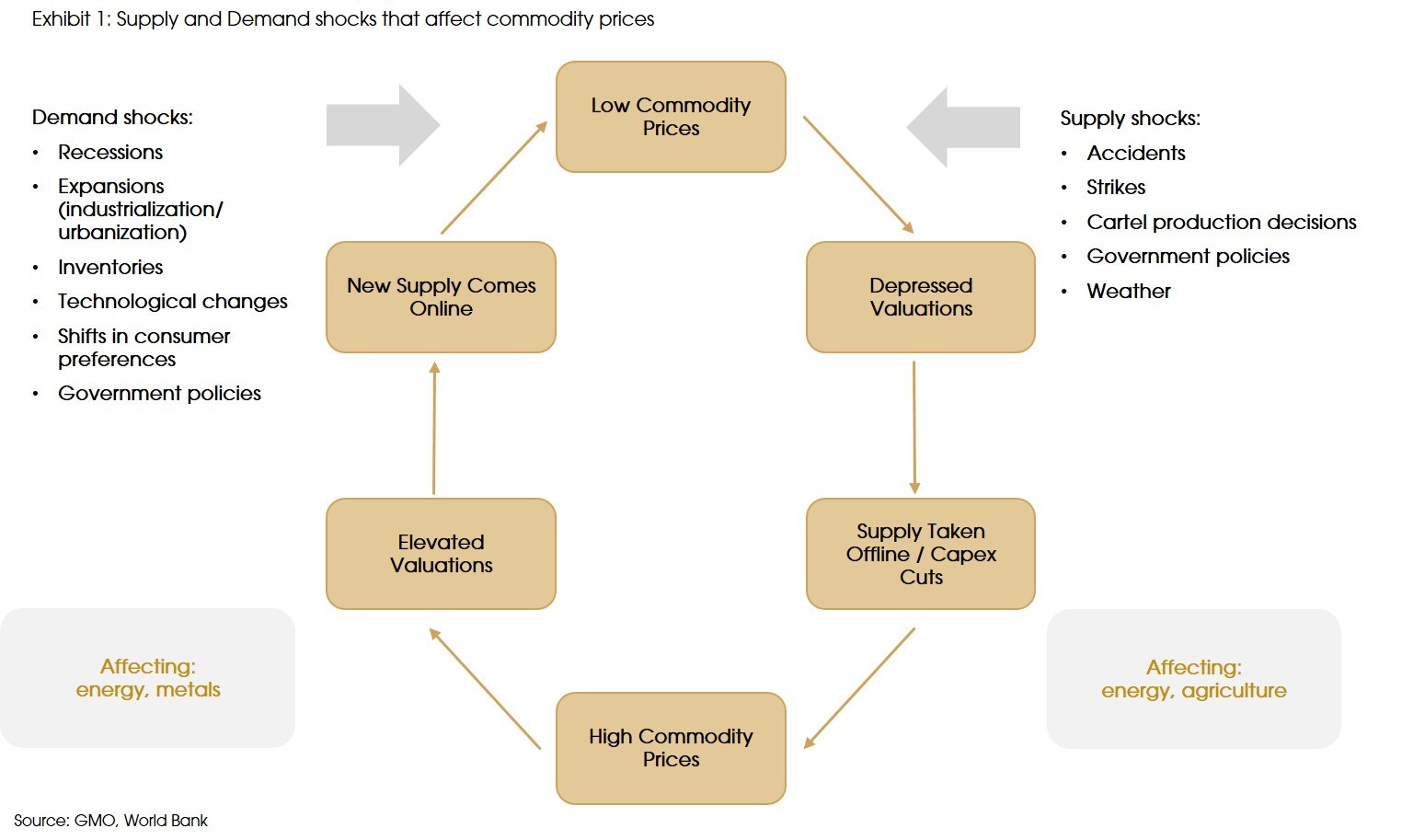

According to the World Bank, the drivers of commodities prices can be categorized into aggregate global demand shocks, commodity-specific demand shocks, and commodity-specific supply shocks.

Aggregate global demand shocks are primarily contingent on macroeconomic conditions, such as economic recessions or expansions, industrialization, and urbanization (e.g., China's expansion in the 2000s).

Commodity-specific demand shocks refer to changes in inventories (e.g., government stockpiling), shifts in consumer preferences, technological development, and government policies (e.g., carbon tax).

Commodity-specific supply shocks include accidents, strikes, conflicts, cartel production decisions, government policies, and weather events.

Within the commodities universe, energy goods and metals are industrial commodities. They have very different supply-demand dynamics compared with agricultural goods and tend to react more to economic cycles (Exhibit 1).

Specifically, prices of agricultural goods are mainly driven by commodity-specific supply shocks, for example, weather, natural disasters, and farmers' decisions, while demand is relatively stable regardless of economic activities.

However, metal consumptions and prices are mostly affected by business cycles and have strong responses to industrial activities. Academic studies have found that demand shocks play a greater role than supply shocks for metal prices, and the impact of aggregate demand (macroeconomic conditions) has been rising over time.

Therefore, although base metals only account for around 7% of global commodities consumption, their prices, especially copper that constitutes the largest share of base metal consumption, are often considered as barometers to measure global economic activities.

Like metal prices, energy prices are affected by similar drivers, such as economic cycles, and their prices tend to move together around major economic events (i.e., recessions and subsequent recoveries). However, compared with metals, energy prices are more responsive to supply shocks. For example, OPEC's production decisions significantly affect oil prices, and geopolitical conflicts triggered three oil crises in history.

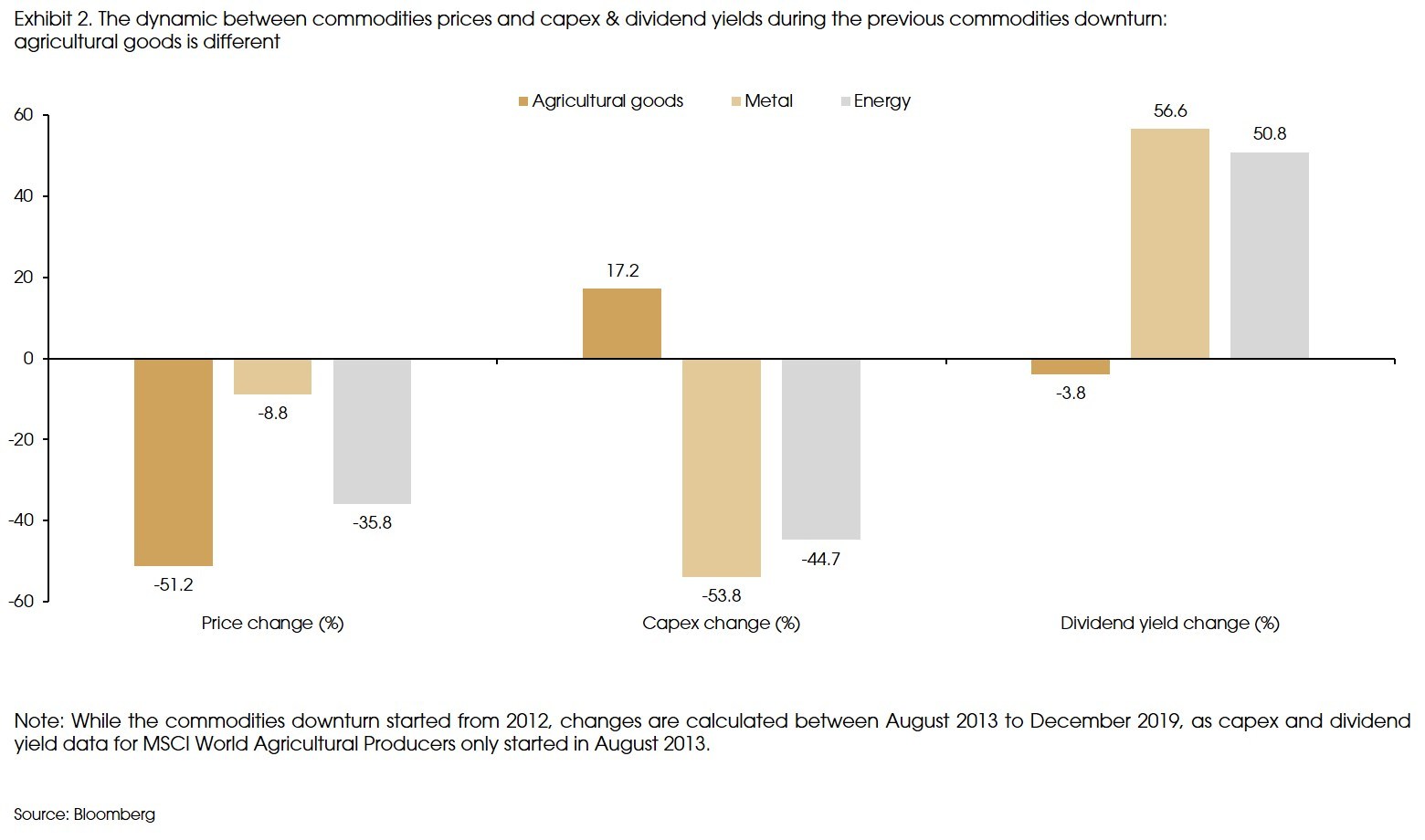

As a result, during the previous commodities downturn, both energy and metal mining companies reacted to the weak demand by cutting back capacity and increasing dividend payments. However, agricultural producers did the opposite thing: capital expenditure increased and dividend payments decreased (Exhibit 2). Such different actions suggest that while energy and metal producers react to the weak demand and falling prices, agricultural producers may actually create them.

Therefore, agricultural goods are more related to their sector-specific supply-demand dynamics, while metals and energy goods tend to move with macroeconomic conditions.

The Macroeconomic Tailwind: Policy Support and Supply Disruptions

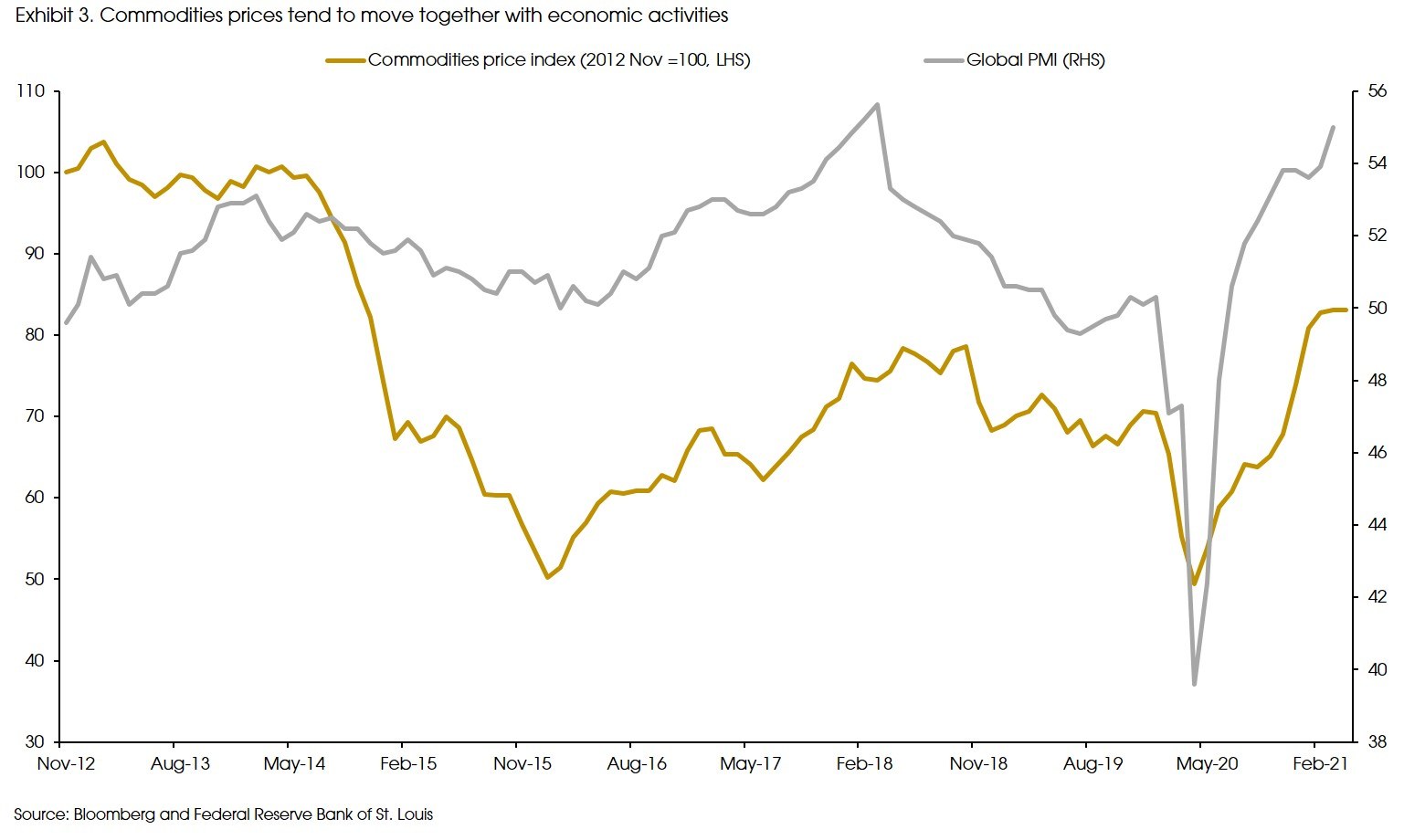

Global economic recovery has been faster than expected last year due to the accelerated vaccination and aggressive fiscal stimulus from governments. The IMF has raised its global GDP growth forecast for this year to 6%. The Fed has also described the US economy as at an "inflection point" and may grow more quickly moving forward. Meanwhile, as the world's biggest commodity consumer, China is already back to its pre-pandemic trend growth.

Therefore, we will probably have a solid and synchronized economic growth. Historically, such upward economic cycles will benefit commodities in general (Exhibit 3).

Moreover, the post-pandemic fiscal supports aim to reduce inequality, achieve carbon-neutral, and boost domestic infrastructure investment, thereby further increasing the demand for commodities.

Specifically, lower-income households benefit more from the government's fiscal stimulus, and they tend to have a higher propensity to consume, especially physical goods, than the higher-income groups. Therefore, while service consumptions are still below the pre-pandemic levels, goods consumptions are already above the pre-pandemic trend in major economies.

Moreover, during the previous cycles, significant infrastructure investments were only seen in emerging markets and were muted in developed countries. However, the post-pandemic fiscal boosts in developed economies aim at large-scale infrastructure and decarbonization investments, such as the US's American Jobs Plan and the EU's Green Deal Investment Plan. These are likely to support higher capital expenditure growth relative to the previous cycle.

Finally, as geopolitical tension between China and the US persists, the two largest economies have accelerated the process of moving key supply chains back to the domestic markets, building and expanding capacities in key industries (e.g., the semiconductor).

The increased demands from physical goods consumption and infrastructure and specific sector-related capital expenditures have all helped restart the manufacturing cycle, which should continue to drive up demand for commodities.

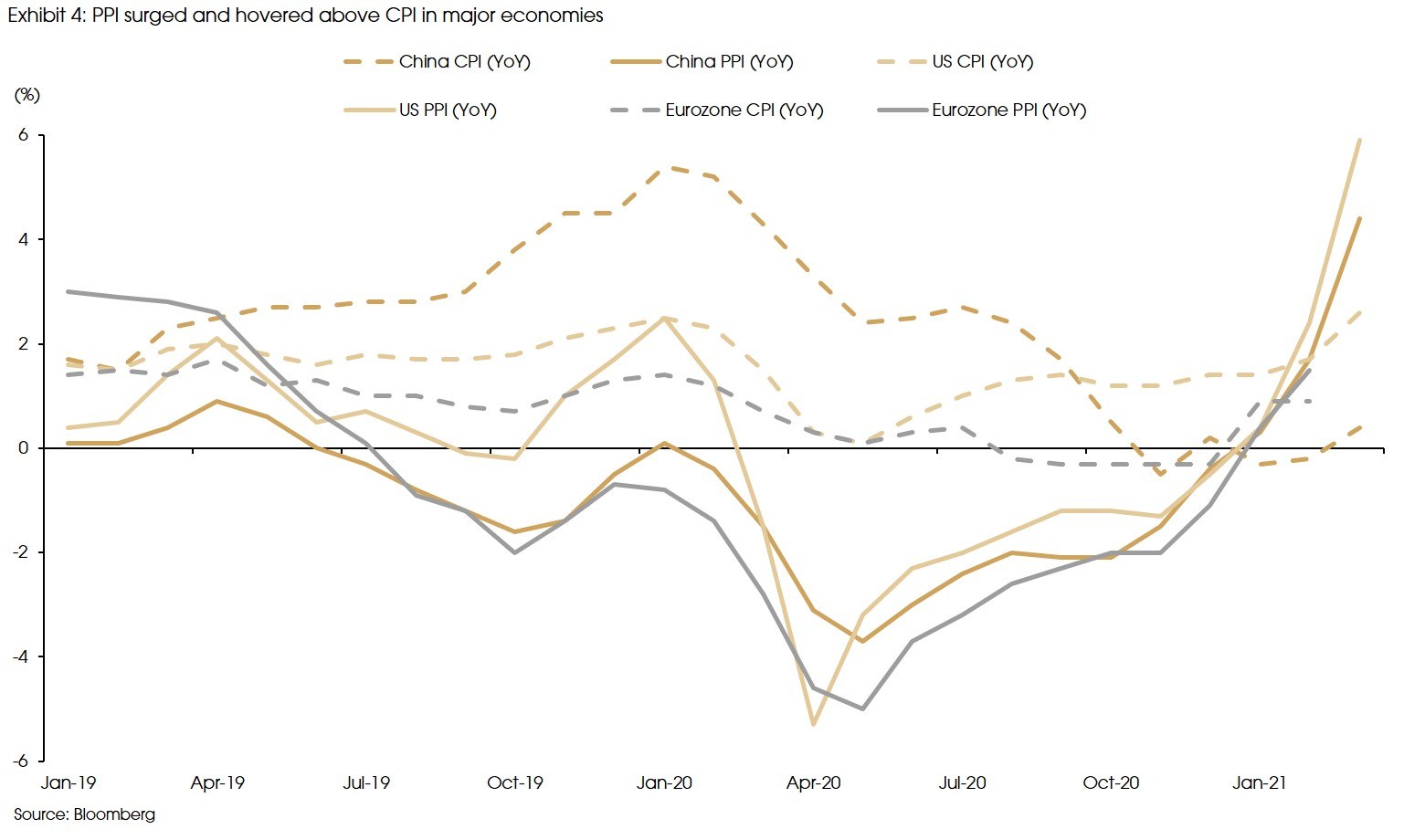

However, the pandemic has generated a notable supply shock to the global economy, from production suspension to shipment disruptions. As a result, PPI surged and kept hovering above CPI, suggesting ongoing supply disruptions in major economies (Exhibit 4).

Moreover, given the decade-long commodities bear market before the pandemic, producers in the energy and metal mining sectors have been cutting capacity. Therefore, given the increasing demand, most commodities markets are in deficit (supply lower than demand). According to the forecast by Goldman Sachs, the only industrial commodity market that is not in deficit this year is zinc.

Such broad-based supply shortages have buoyed commodities prices since the second half of last year, and the commodities upward cycle may sustain going forward.

Granular Views: More Bullish on Metals in the Longer-Term

In general, both the macroeconomic conditions and the commodity-specific supply-demand profiles are favorable for commodities. However, we expect industrial commodities to benefit more from the current economic upward cycle, and from a longer-term view, we are more bullish on metals than energy goods.

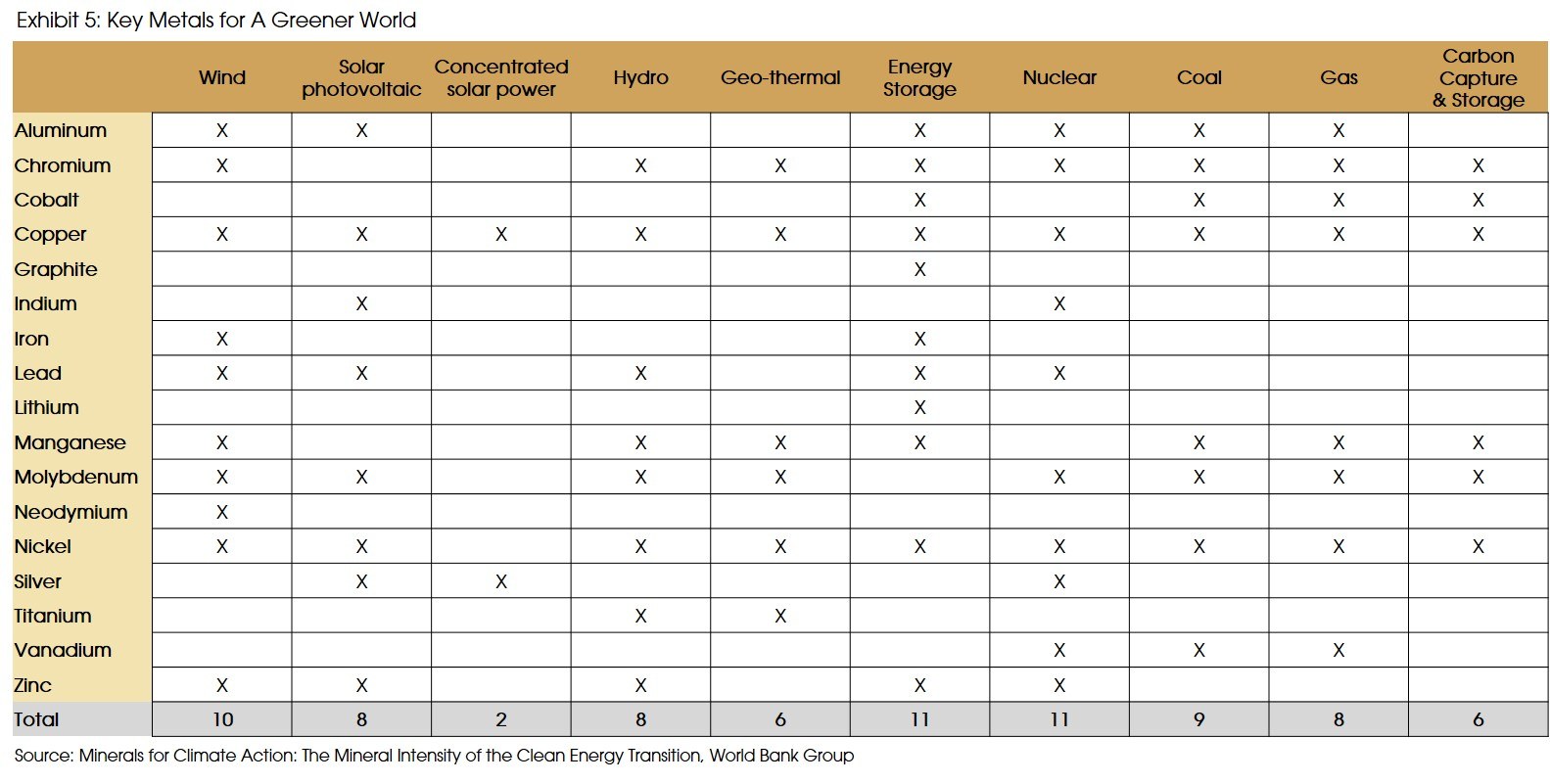

The previous industrial revolutions were powered by fossil fuels, while the current "green transition" or the decarbonization revolution relies heavily on metals. Base metals such as copper, zinc, aluminum, and nickel are heavily consumed in the major components of the non-fossil fuel or alternative energy sources and infrastructure (Exhibit 5).

For example, an internal combustion engine (ICE) vehicle uses 23 Kg of copper on average, while an electric vehicle requires 57 Kg. According to the International Copper Study Group, demand for copper is expected to increase from the current 25 million tons to nearly 70 million tons in 2050, of which 10 million tons of increased demand will be from alternative energy sectors.

In short, transition to green energy will steadily increase metal consumption while generating downward pressures for traditional energy in the long run.

Moreover, even though metal prices are returning to the previous highs, there have been limited new supplies in the market. Unlike the energy sector, there has been no major productivity breakthrough in the base metal mining sector over the past two decades. Long lead time for project development and divergent capex suggests that supply of metals cannot react quickly to meet demand, and capacity resumption may take long (e.g., 2-3 years for cobalt miners).

Also, the mining sector is still relatively labor-intensive. Thus, when rebuilding capacity, labor/wage disputes will increase, leading to further supply uncertainty. Furthermore, there has been increasing focus on capital discipline among mining companies, which might continue to limit supply.

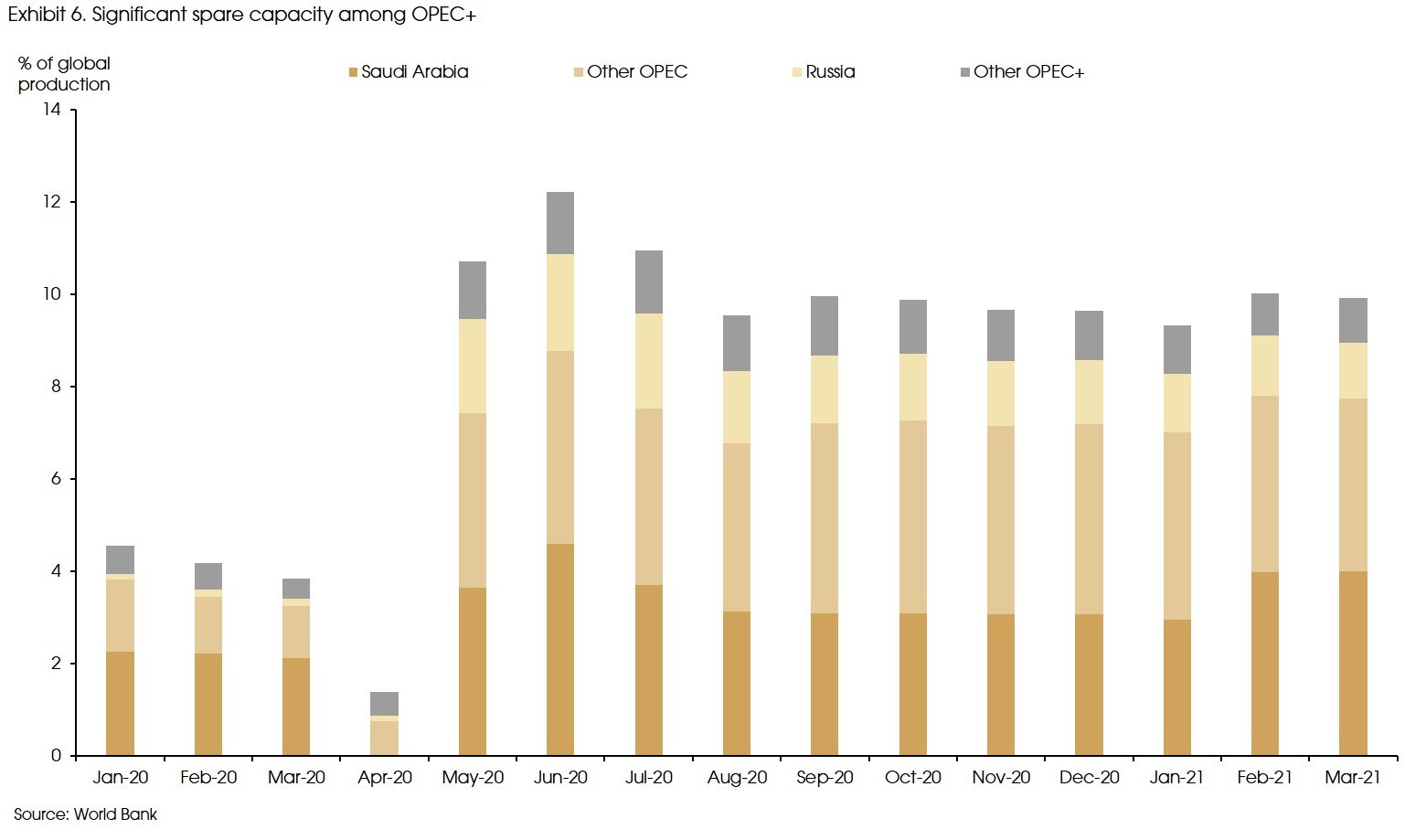

Therefore, although both energy and metal mining capacities have declined, energy, or more specifically, the oil sector's spare capacity has stayed high and can be quickly put into use (Exhibit 6). However, metal miners (e.g., copper, aluminum) face higher risks of supply scarcity (according to data from Goldman Sachs).

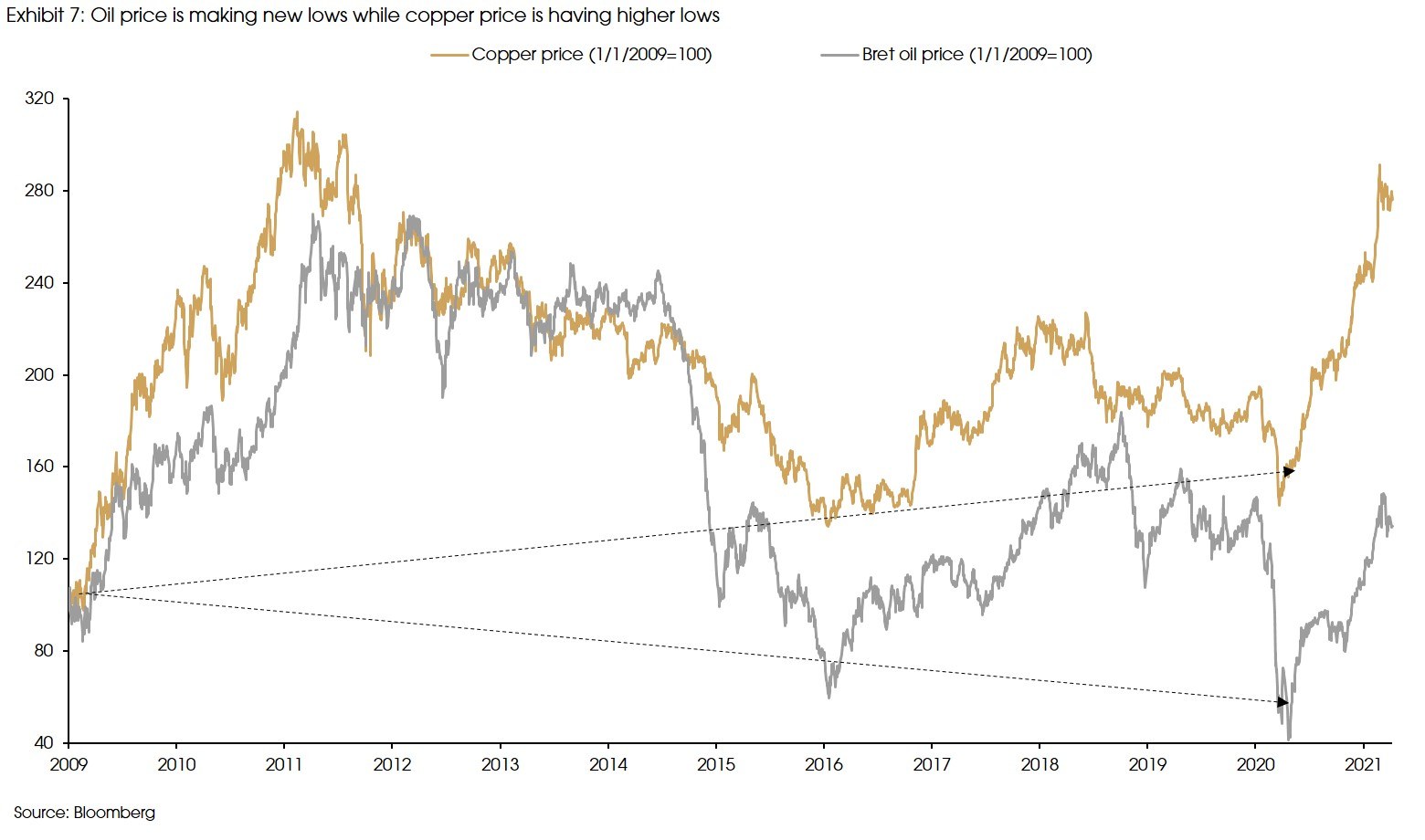

In sum, the demand-pull from the "green transition" and the bottleneck from supply have led to the different price performances between base metals (copper) and energy (oil). Oil prices have shown a pattern of lower lows, while copper has been making higher lows (Exhibit 7).

Therefore, compared to energy goods, the case for a multi-year upward cycle of base metals is stronger, in our view.

How to Take Opportunities of the Upward Cycle in Commodities?

As mentioned above, we believe that metals will benefit from the economic recovery more than agricultural goods and will have more tailwinds than energy goods.

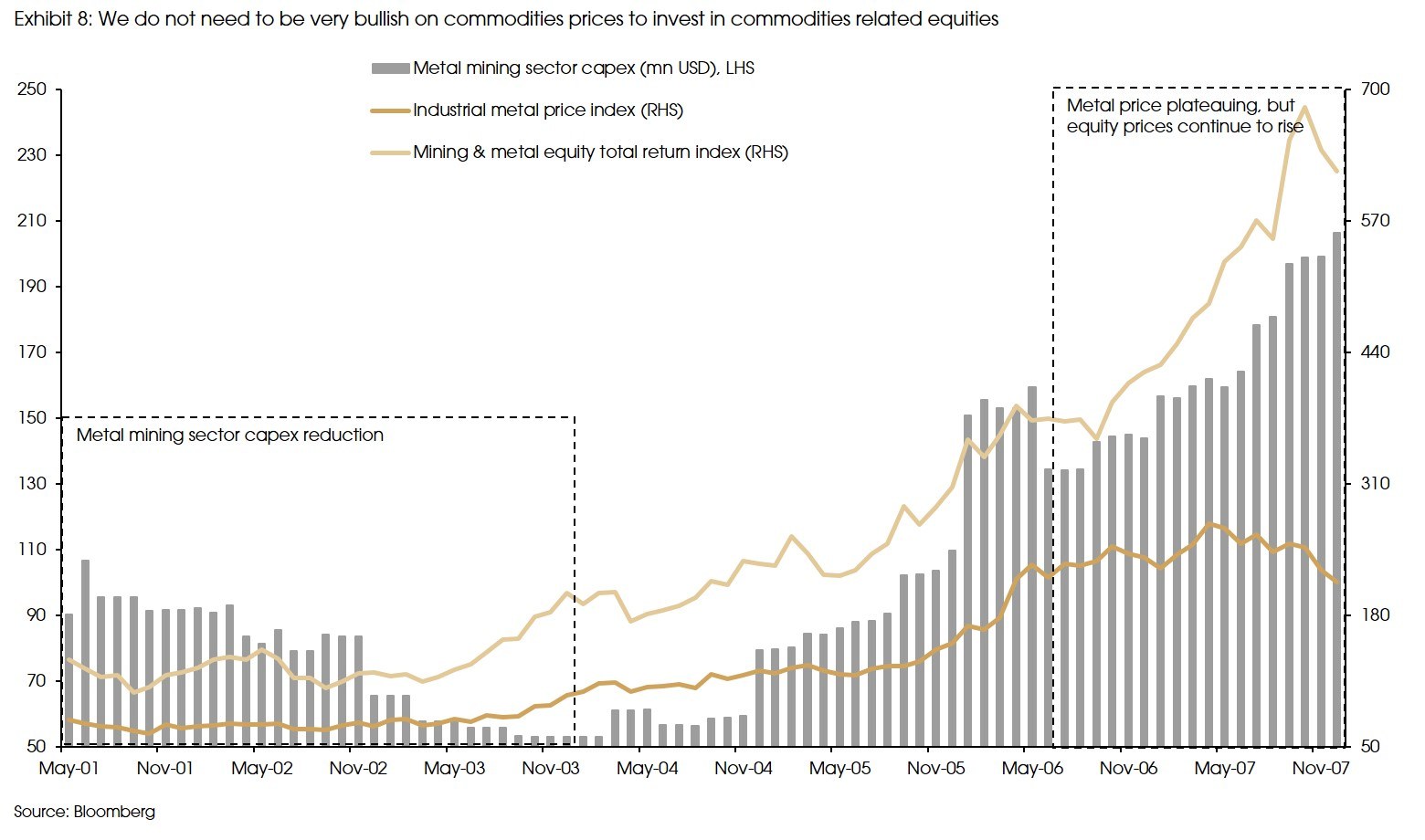

However, investing in commodities is not straightforward, and commodities-related equities can be an option. Commodities prices are volatile, but falling commodities prices do not necessarily lead to falling stock prices of commodities-related companies: decent margins, notable market shares, higher dividend yields, and solid balance sheets are all potential factors supporting equity prices, even during a downturn.

Metal prices peaked and range-bounded between 2006 and 2008, but metal mining companies' share prices still gained more than 70% during this period (Exhibit 8).

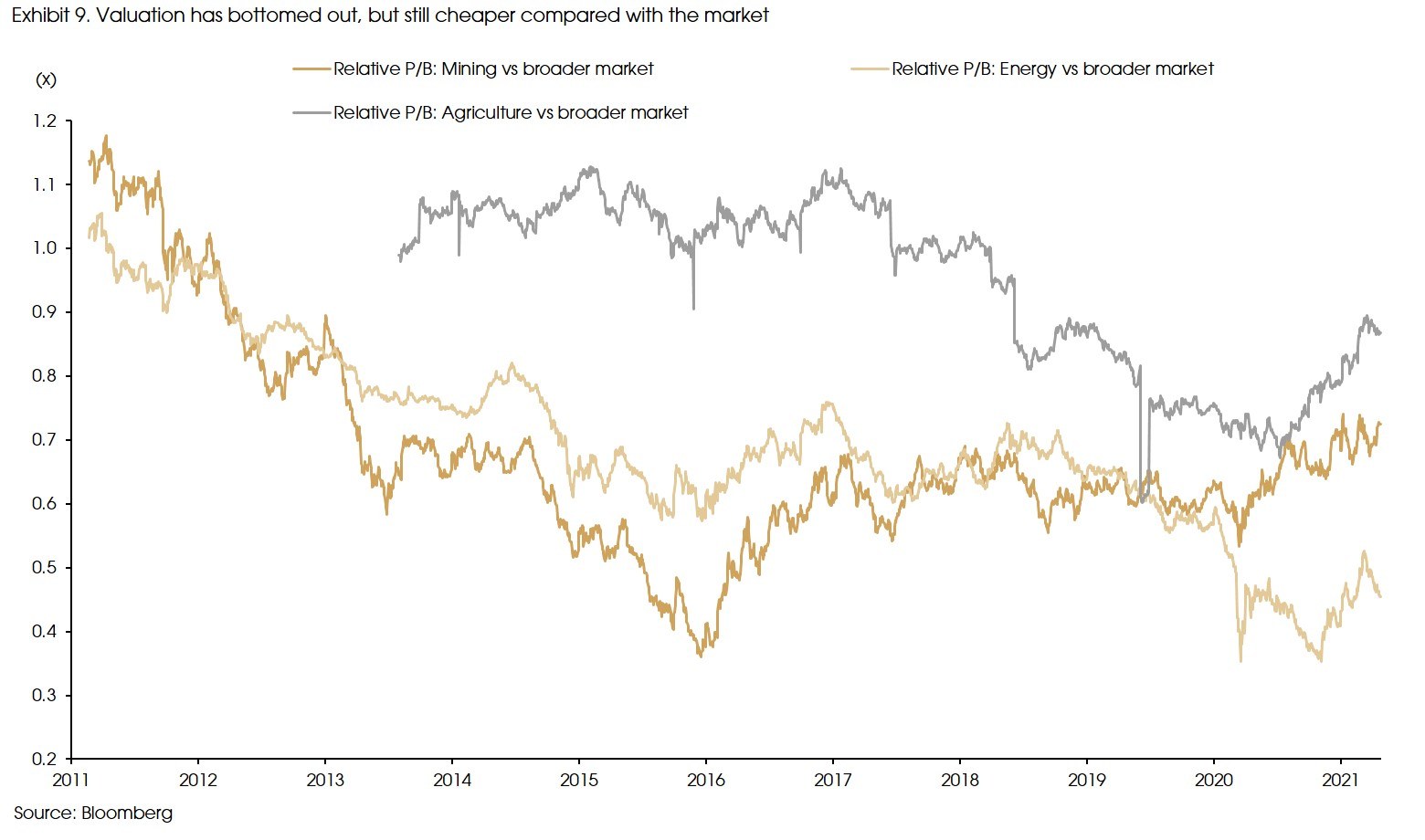

Moreover, currently, the overall mining companies' valuation is still under the long-term level, suggesting some rerating opportunities, and the low valuation can also be a good buffer against rising interest rates and market volatility (Exhibit 9).

Some final words on the downside risks: 1) commodities are a very heterogeneous asset class, different commodities have very different supply-demand profiles, even within the same category (e.g., base metal); 2) China is the biggest consumer of commodities, potential monetary tightening, and moderated growth in China will both have significant impacts on commodities prices; 3) other factors that affect global economic recovery will also have an impact on commodities, for example, the resurgence of the pandemic, tax hike from the US, and QE tapering; 4) a reverse of the weak dollar trend will also put downward pressures on commodities.

Sources: Blackrock, Federal Reserve Bank of St. Louis, GMO, Goldman Sachs, International Copper Study Group, Morgan Stanley, World Bank and CIGP Estimates.