CIO Viewpoint: China in 2022 - Bottoming Out?

2021 has been an eventful year for China. The Chinese government released a number of “de-risk” and “rebalance” policies, such as the “double reduction” document on the After-School-Tutoring (AST) sector (turning the sector to non-profit), the more than 40 regulatory policies on the internet sector, the “red lines” and “limits” to restrict real estate-related activities, and the decarbonization targets which led to a power shortage.

Even with the government’s track record of imposing a strong influence on the economy, such a combination of policy intervention is unprecedented. It has led to significant moderation in economic growth and dramatic volatility in the capital market with deteriorated confidence.

The question now is: will we see a turnaround in 2022? From the top-down view, we see encouraging signs, such as the shift in policy stance and the historically good performance of the Chinese economy and markets in the years with the Party Congress. However, from a bottom-up view, we still see a number of risks on the downside, for example, the very restrictive “zero-tolerance COVID policy” and the hard-landing risks in the property sector. This is why we referred to China as a “wild card” for 2022 in our Outlook.

We will try to elaborate on such upsides and downsides in this letter.

The big picture: growth to stabilize lower

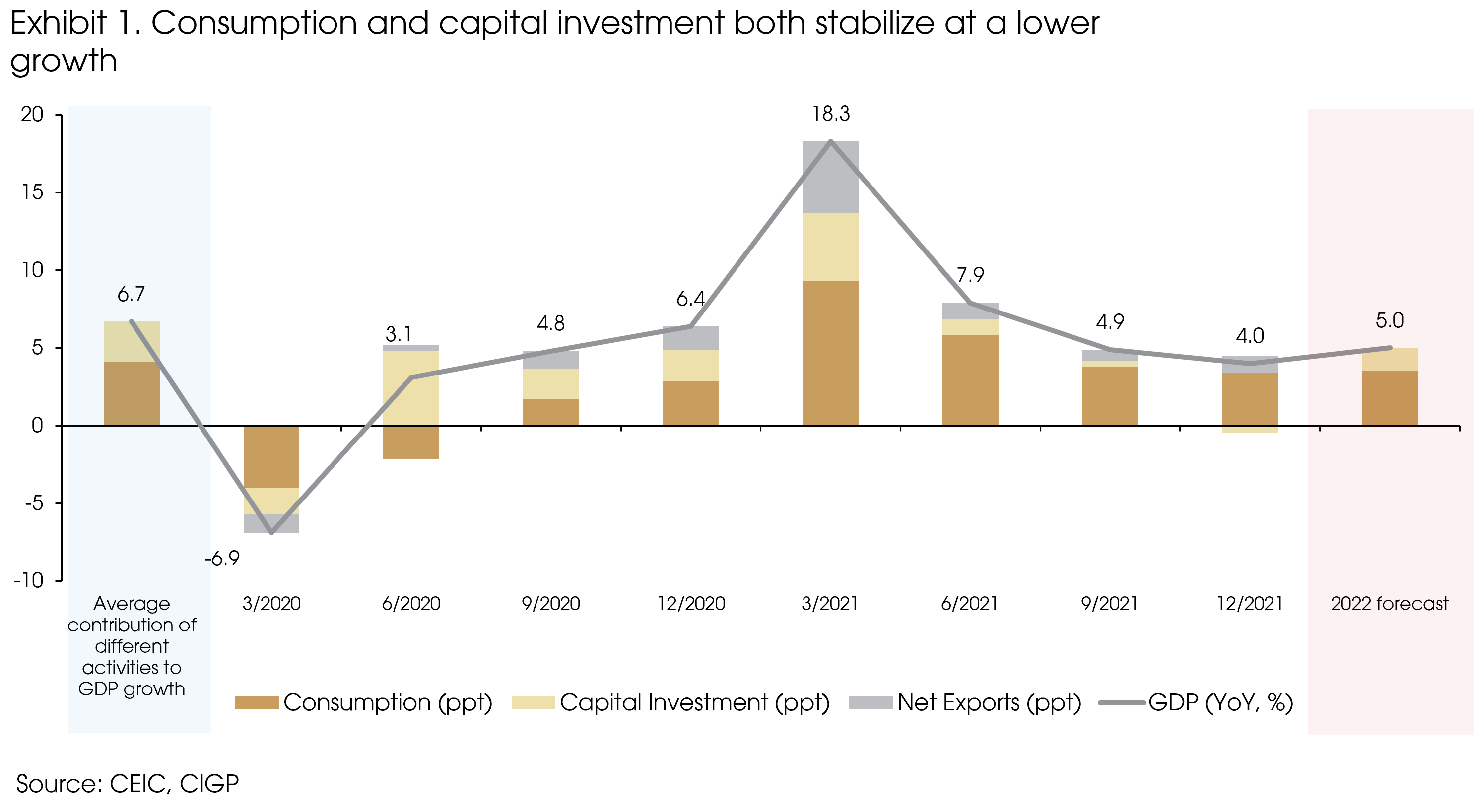

For the whole year of 2021, although the headline GDP grew by 7.8% based on the low level in 2020, growth significantly slowed in the 2H, due to the tightened credit and fiscal conditions, as well as the regulatory reset in specific sectors. Quarterly GDP growth dramatically declined from 7.9% YoY in Q2 to 4% YoY in Q4, far below the government’s “above 6%” target (Exhibit 1).

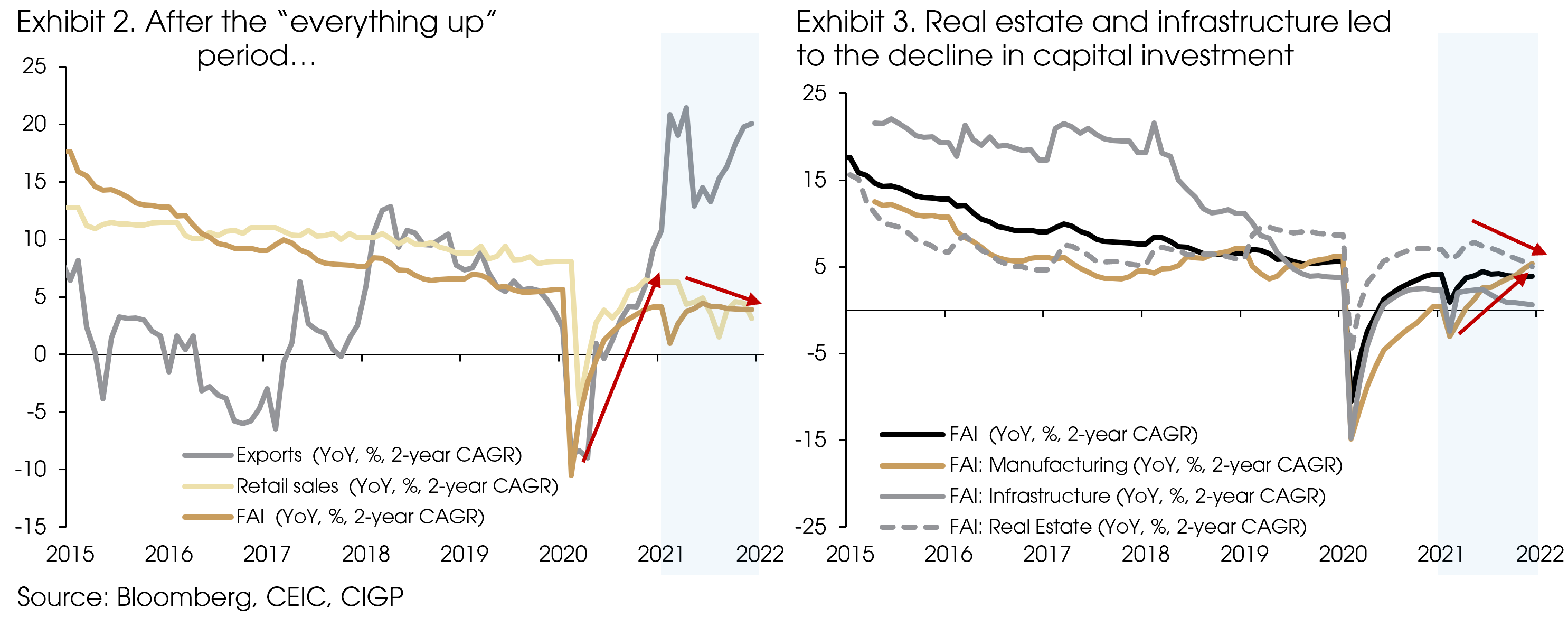

The economic slowdown was broad-based, from household consumption (indicated by retail sales) to infrastructure and property investments. The only sectors that have been relatively holding up well are manufacturing investment and exports (Exhibit 2 and 3), supported by the strong recovery of the overseas economies and the persistent supply chain disruptions.

Given the rising stress in the economy, the Chinese government finally shifted its target from policy normalization to promote economic development, as stated in last December’s Politburo meeting and the Central Economic Working Conference.

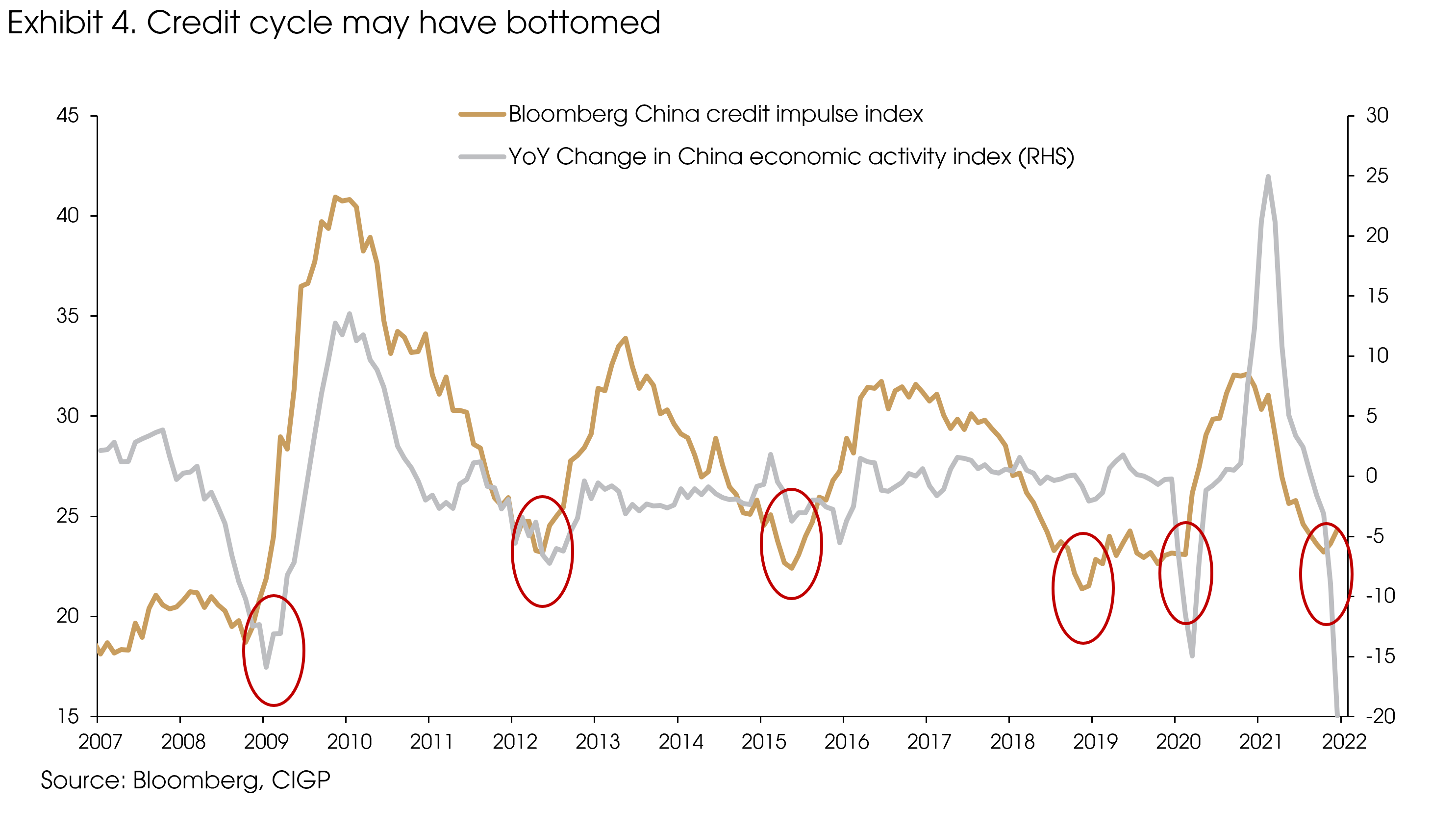

Easing measures followed afterward, such as the 50 bps Required Reserve Ratio (RRR) cut and three benchmark interest rate cuts, suggesting that China’s credit cycle may have already bottomed. Historically, there is a positive relation between the easing credit cycle and improving economic activities (Exhibit 4).

Specifically, infrastructure investment may pick up given the more expansionary fiscal impulse. Due to the ultra-conservative fiscal stance last year, the approval of many infrastructure projects was suspended (estimated at RMB 1 trillion by Morgan Stanley), but they could resume this year.

Meanwhile, although the deleveraging and de-risk policies in the real estate sector will continue to restrain investment, the easing credit conditions may help to relieve a meaningful part of liquidity stress in the sector, enable viable companies to continue operating, and support the business and financial conditions of the real estate-related upstream and downstream sectors. Moreover, the policy support in building affordable housing may also help to stabilize real estate investment.

Therefore, for the 2022 GDP growth, the biggest “delta” will be the acceleration in capital investment growth (Exhibit 1, “2022 forecast”).

Household consumption should also recover, supported by the trickle-down effect of policy easing and the solid exports growth, through stronger employment and higher wage growth.

Our major concern here is the “zero-tolerance” COVID policy, which triggers massive lockdowns upon only mild outbreaks. The Chinese government faces a dilemma. On one hand, the recent spread of the Omicron Variant within the country suggested that the highly restrictive policy could not prevent a local outbreak. On the other hand, as the government has refused to import mRNA vaccines, there is a significant risk if the government eases border control.

We only expect moderate ease of domestic COVID policies in China, probably after the Winter Olympics. The continued restrictions will cap consumption growth.

In the longer term, economic growth should decline further and stabilize at a lower level compared with the past 5 years, due to the decarbonization process (to reduce the emission-heavy sectors), the property deleveraging, and the tightened regulations on the internet and education sectors. These structural reforms are here to stay and will inevitably take a toll on growth in exchange for a more balanced long-term stability.

Even with a bottoming-out credit cycle and a pro-growth shift in policy stance, it takes time for the real economy to respond. Meanwhile, the structural changes will restrain the short-term growth for a number of sectors, which inevitably creates near-term risks and uncertainties to the top-down encouraging picture.

Chinese equities: cheap valuation, “election year” effect, but…

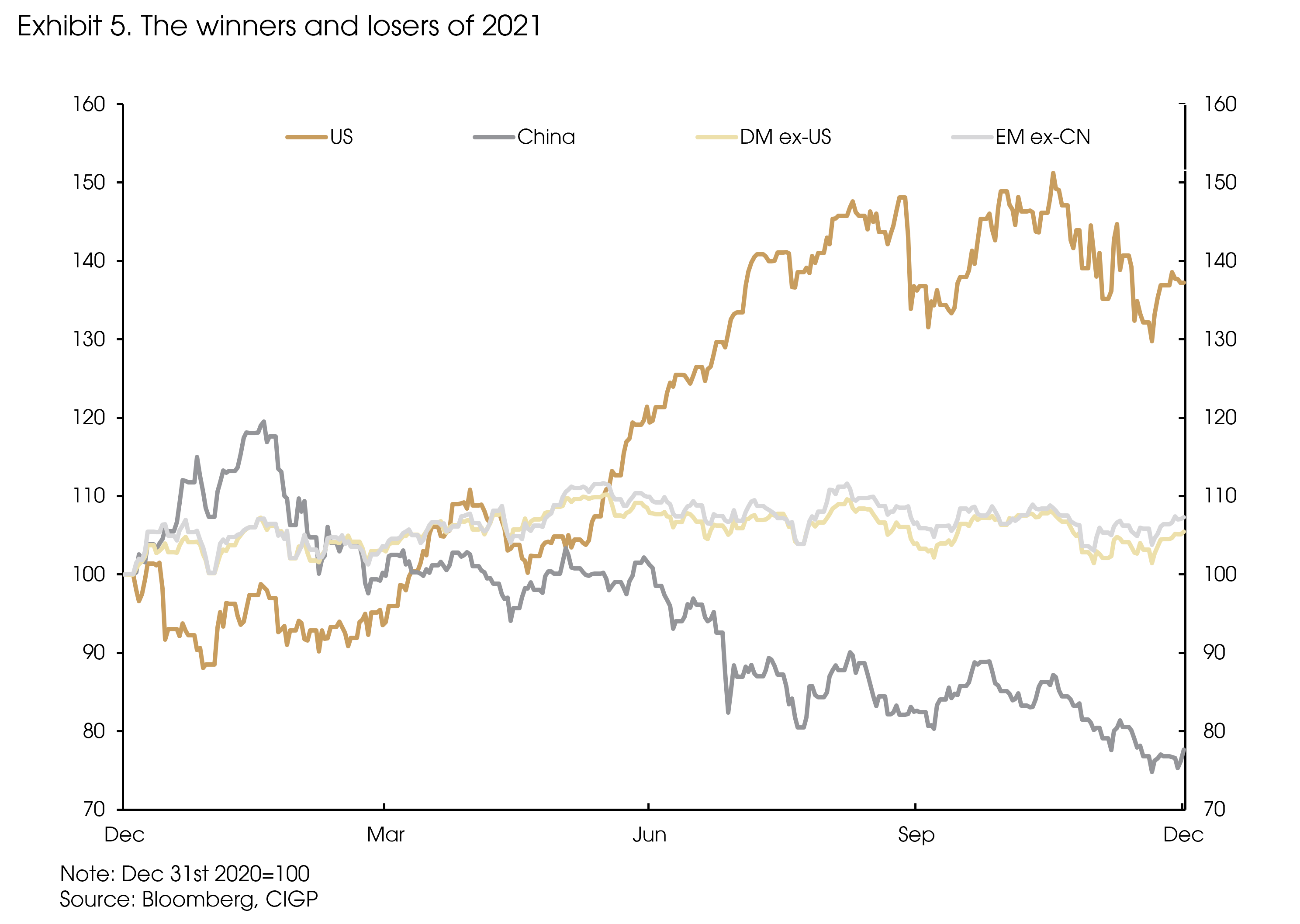

The Chinese equity market started 2021 with good momentum, outperforming most other stock markets during the first two months. However, the structural reform-related tightening and rounds of regulatory crackdowns among different sectors led to a huge negative impact on market sentiment and the following ten months of the market downturn (Exhibit 5).

Again, from the top-down view, we see an interesting picture on the Chinese market, which is perfectly in line with the old wisdom: “when economic growth is weak, valuation is cheap, market sentiment is bearish, and policy is easing, it suggests an entry point…”

Moreover, if we consider the political cycle, it becomes even more interesting: the Chinese markets (both onshore and offshore) always have good performance during “election years” (the years with Party Congress).

That said, a closer look at the market brings concerns, at least from several aspects.

First of all, the Chinese markets do have relatively lower valuations compared with others: the current MSCI China Index and the Hang Seng Index are both valued at around 11x PE and the onshore market at 13x, much lower than that of the S&P 500 (19x), and the Euro STOXX 600 (15x). However, they are always lower. Seen from the changes of valuations, we cannot draw the conclusion that the Chinese market has become cheaper after the downturn in 2021: the valuation of the US market compressed from 27x to 19x, European market compressed from 23x to 15x, while the Hang Seng Index compressed from 14x to 11x, not very different.

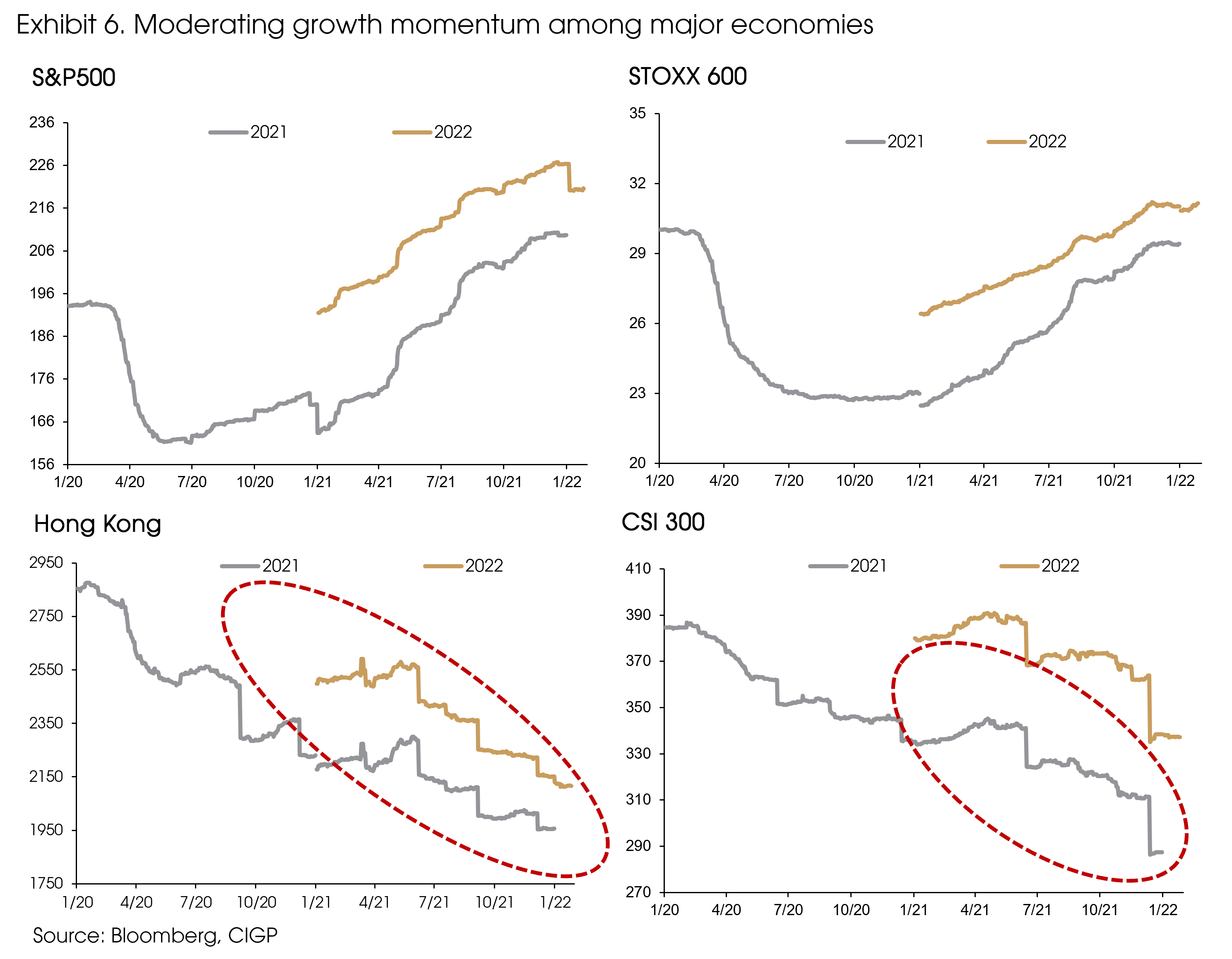

The main difference is from earnings (Exhibit 6). Earnings of the Chinese markets have been continuously downgraded since 2021. Meanwhile, earnings of the US and the Euorpean markets were both significantly adjusted higher.

Even though the policy easing could boost both earnings (through the improved economic growth) and valuation (through increased liquidy in the market), building the base for a rebound, we still need to mind the downside:

- The recently aggressive tone from the Fed has increased the odds of a hawkish monetary normalization in the US. Although we do not expect monetary tightening to overturn the upward trend in the market for now, the risk has notably increased. Historically, whenever the US market fell by more than 10%, other markets fell deeper.

- As the policy target has turned to pro-growth this year, the downside for the sectors with both depressed valuation and earnings have become limited. On the other hand, from the bottom-up view, the regulatory reset has already compromised companies' business models and earnings outlook, which will not recover any time soon (some property companies may face increased credit risks going forward). New growth models need to be built and new stories need to be told for the badly hammered companies to regain momentum.

- The potential escalation of the US-China tension still merits close attention, especially before the US midterm elections. The risks of delisting the Chinese ADRs at a faster pace and adding more Chinese companies to the US’s entity list will add to further downside in the market.

The real estate sector: turmoil may continue but with limited hard-landing risks

China’s real estate and construction boom started after the housing reform in the 1990s, before which the public housing system led to a significant supply shortage in the market. After the reform, there has been a massive construction boom, partially to compensate for the cumulated housing shortages.

The property market boom also reflected the robust housing demand, leading to surging housing prices. Property price to income ratio of 1-tier cities are all at above 30, among the Top 10 in the world (according to Numbeo).

As a result, whether there is an overheat or bubble in China’s property market has become a popular topic. However, one thing to point out is that housing oversupply and dramatic price gains can co-exist only if mortgage lending standards are loose, as what happened in the US before 2008, or Japan in late 1980s.

It is not the case in China: mortgage lending standards have been very stringent. Mandatory down payments have never been lower than 20%, and 60% for a second home. The mortgage loan rate is high at 5-6%. Whether the Chinese housing market is in a massive bubble is, at least, still debatable. The Chinese government took action regardless.

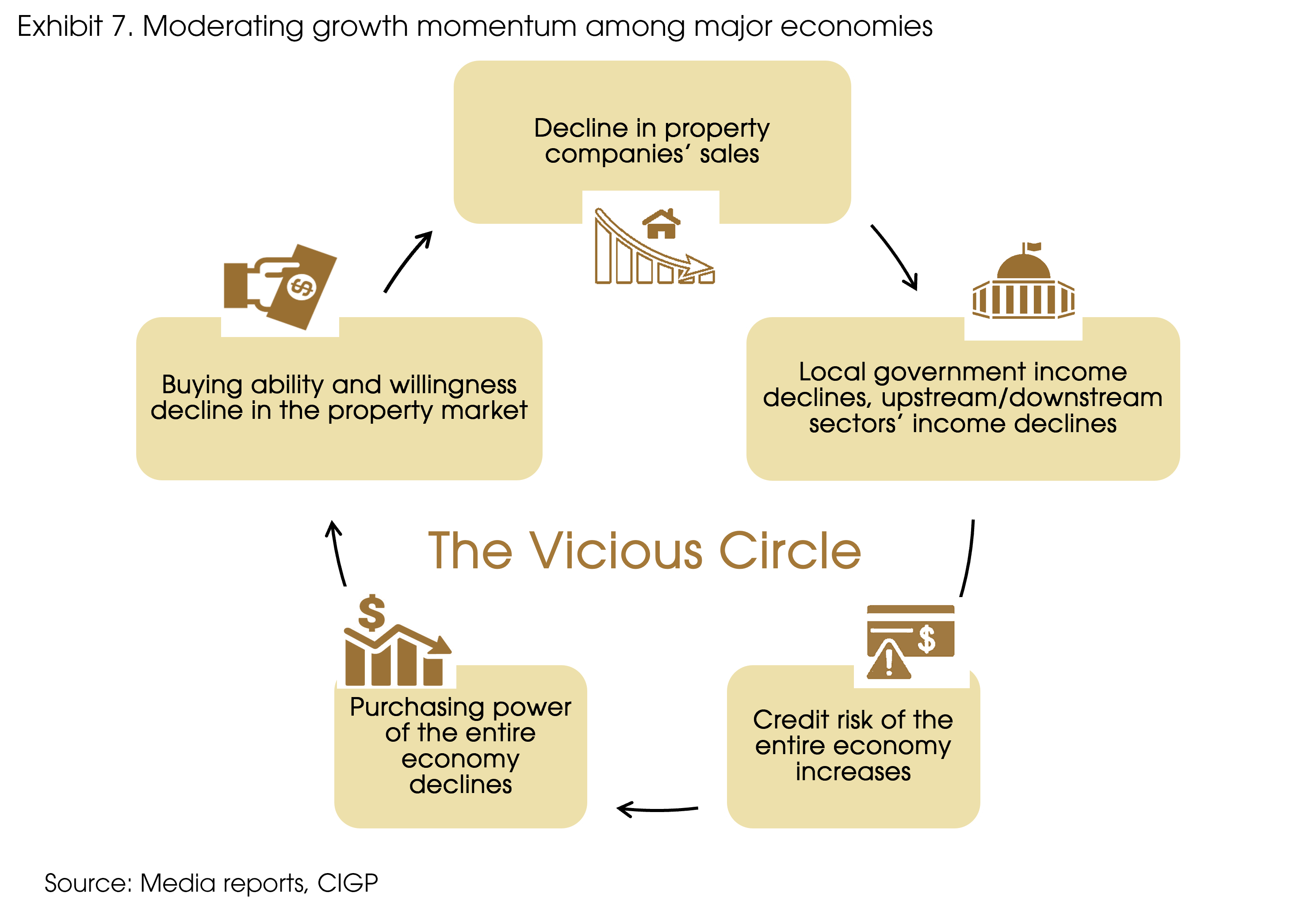

As a highly levered business by nature, a sudden stop of funding flows can easily threaten even the most financially conservative developers, spreading the stress to the entire sector, triggering a vicious cycle in the broader economy, and leading to hard-landing risks (Exhibit 7).

Given the significant impact, the government finally released a number of policies fine-tuning to continue to provide liquidity in the sector and to prevent contagion effect on other sectors, such as the acceleration of mortgage loan approval, rate cuts, marginally loosened restrictions on developers’ funding channels, and the plan of increasing affordable housing.

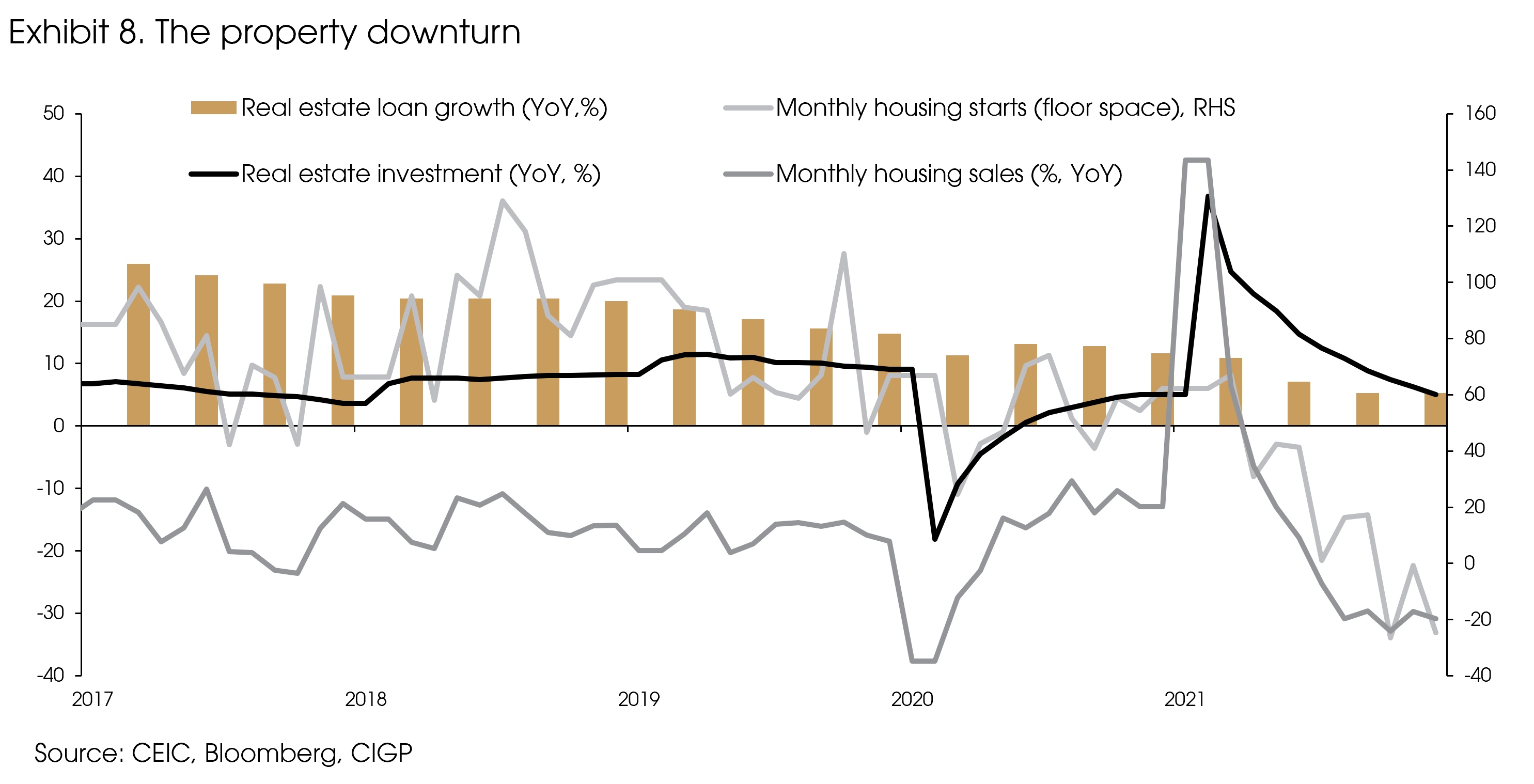

As a result, we think that the worst time in the property market may have already passed. Nevertheless, given the massive downturn in almost every aspect of the sector, from loan growth to real estate development investment, and from housing starts to property sales (Exhibit 8), it takes time to recover. We cannot exclude aftershocks in the sector.

The internet sector: policy headwind to stay, but long-term potential is intact

Anti-trust moves on platform companies, regulations on fintech, data security inspection, labor and minor protection, and the removal of favorable tax treatments may continue to affect the internet sector (Exhibit 9).

However, fundamentally, the digital economy, online gaming, e-commerce, online entertainment is the future trends with solid and still unsatisfied demand in China. As a result, we still see the sector as a long-term play, although the regulation headwind has increased the near-to-mid-term growth uncertainty.

In addition, the internet sector has been developing since early 2000, but there was little regulation until 2018. Given that many names have become trillion RMB groups, with broad-ranging business scopes, imposing regulation seems unavoidable in the long run.

Looking ahead, although we cannot rule out further regulation rollout, the market reaction should be milder.

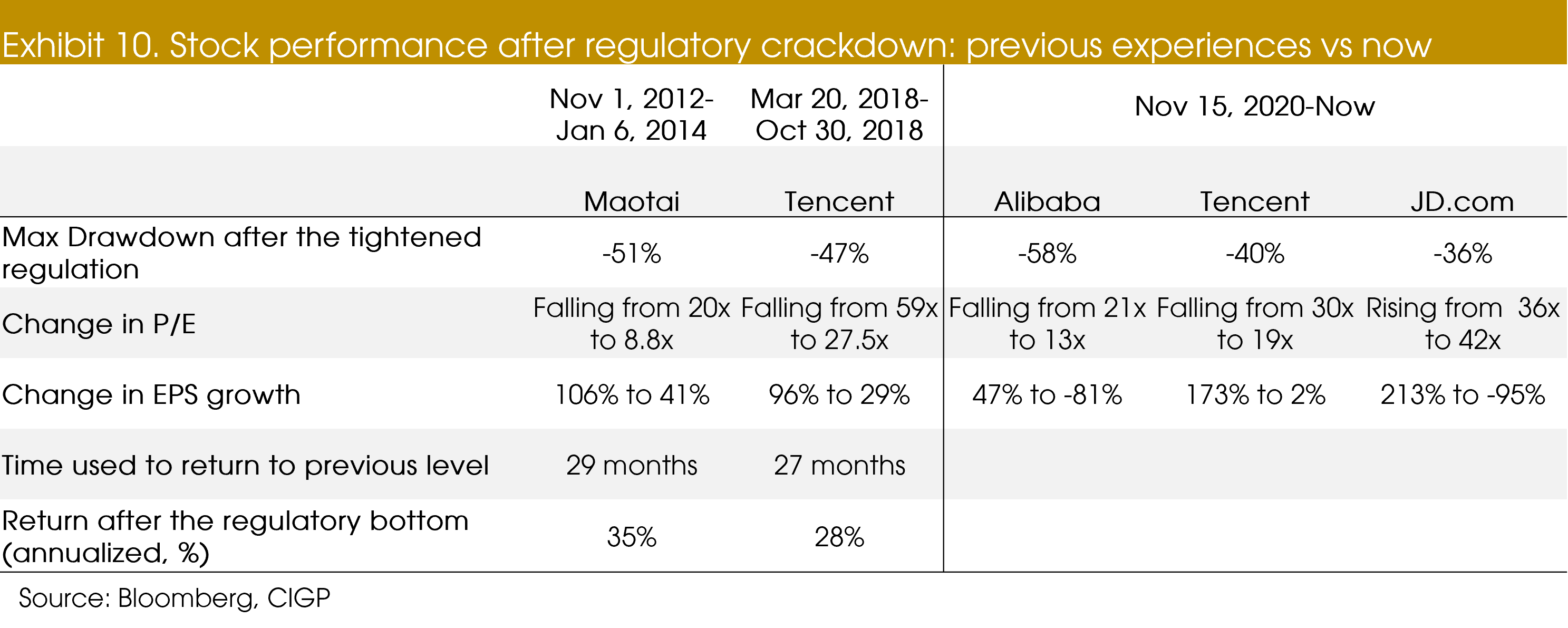

Seen from the previous regulation crackdowns on specific sectors and companies, usually, it will lead to around 50% drop in share prices, and takes 2-3 years for the affected companies to adapt (in both earnings and valuation) before returning to the pre-regulation price levels. Last year’s regulation crackdown has already resulted in about 50% correction of the share prices in many internet names, suggesting a reduced downside.

Going forward, how to find a new growth model under the new regulation framework might be the key to making the future winners. Given the intact long-term potential demand within the sector, we will keep the names that we like on the watch list.

Healthcare: high valuation and policy risks remain as key concerns

The National Reimbursement Drug List (NRDL) has always been a headwind for China’s pharmaceutical companies. Drugs that are included on the list usually have a 50-60% reduction in price, but with the government’s Volume-Based Procurement (VBP) in return.

Looking ahead, there might be new challenges at the regional level for upcoming contract renewals of the current drugs under VBP and potential cross-regional price referencing, which might trigger further price reductions.

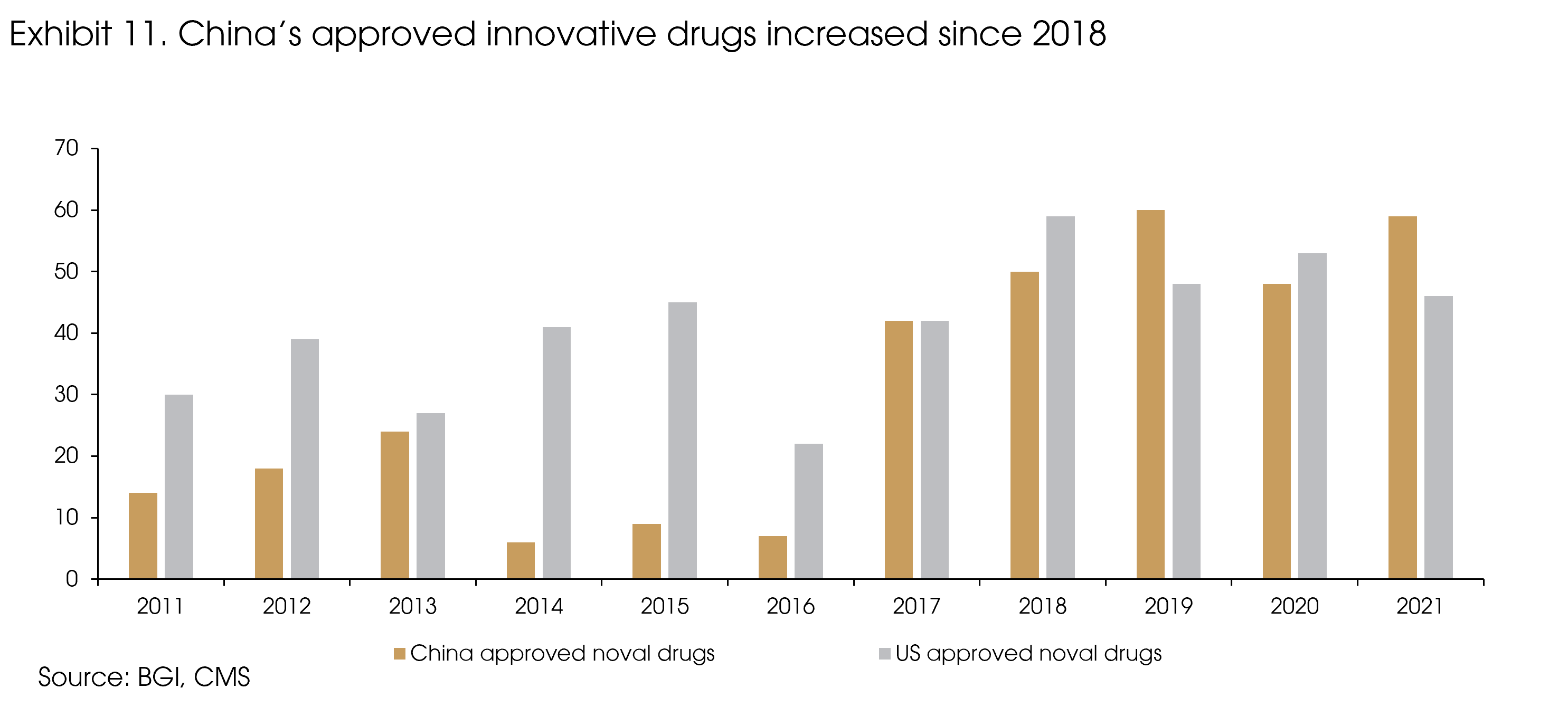

However, as the yearly revision of the NRDL and the VBP (~2-3 rounds per year) become the new normal, its market impact may moderate. Despite the pricing dilemma, if the rate of negotiation success remains high (~60-80% in 2019-21), it might further encourage innovation (Exhibit 11).

Similar to the internet sector, we think that the development of innovative drugs is a long-term play. Although they may be affected by policy risks, such as drug price reduction or potentially geopolitical tensions, we are positive about their long-term growth prospects.

The larger-cap biopharma stocks might be more resilient given their rich cash position and eventful pipelines (for example, the FDA’s potential approval of several Chinese drugs). Meanwhile, we are still positive about CXO names’ ability to deliver solid earnings growth in the coming years, backed by the clear visibility of their backlogs and ongoing innovation trends. That said, high valuation remains a concern given a more volatile market.

Renewable energy: policy tailwind to stay

We have our long-term belief in the energy transition, even if the near-term tailwind has switched to the old energy sector, given the energy supply shortfall last year.

For China, the renewable energy sector is an important part of the structural reform, thereby having a significant policy tailwind. For example, even with the credit and fiscal tightening last year, the green capex and green loans still increased.

The renewable energy sector has many sub-sectors, categorized by different energy sources, e.g., solar, wind, nuclear, and hydrogen, or by different stages along the value chain, e.g., materials, parts, and downstream operators. Each sub-sector has its own cycle. Please refer to our previous report on the renewable energy sector for more detailed views.

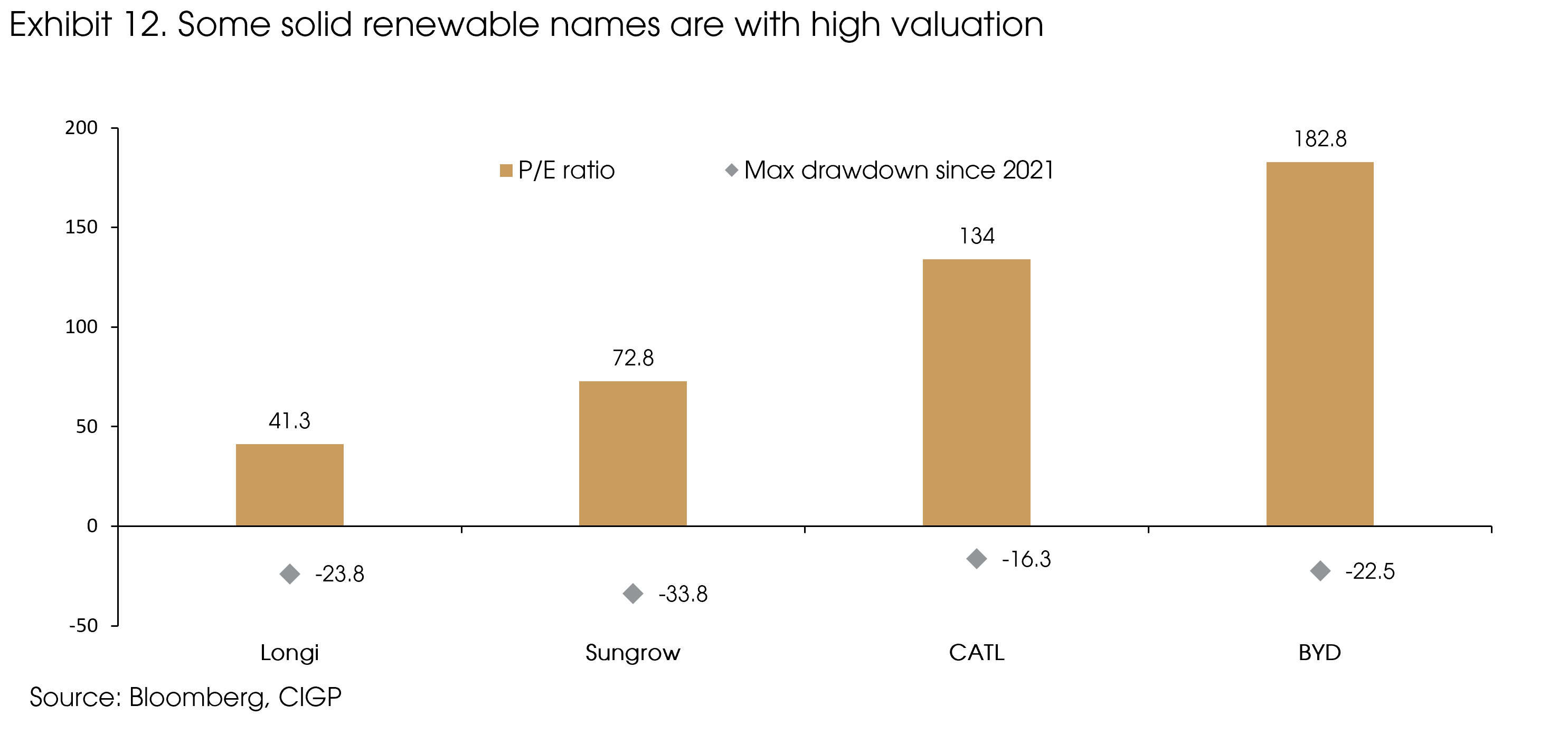

Even with the policy support, it is unlikely to benefit every sub-sectors. We prefer the sectors that are more to the upstream and less cyclical, e.g., some solar parts names. However, for the solid names that are on our watchlist, most are with high valuations and have not corrected as significant as the names in other sectors that we like (Exhibit 12).

We see interesting opportunities in the Chinese market, given the favorable policy shift and the notably “cheaper” valuation compared with other markets. Nevertheless, risks are associated: even if the Chinese market will have a meaningful rebound this year, it will not be a one-way upturn and volatility will remain high.

We expect to see potentially domestic disruptions from the lingering growth concerns in 1H 2022 and rising external volatility, especially from the Fed tightening process and the US mid-term elections, in 2H. Overall, we are cautiously optimistic about China.

Sources: Bloomberg, CEIC, Companies' Reports, CMS, Media Reports, CIGP Estimates