CIO Viewpoint: China - A Series Of Critical Junctures

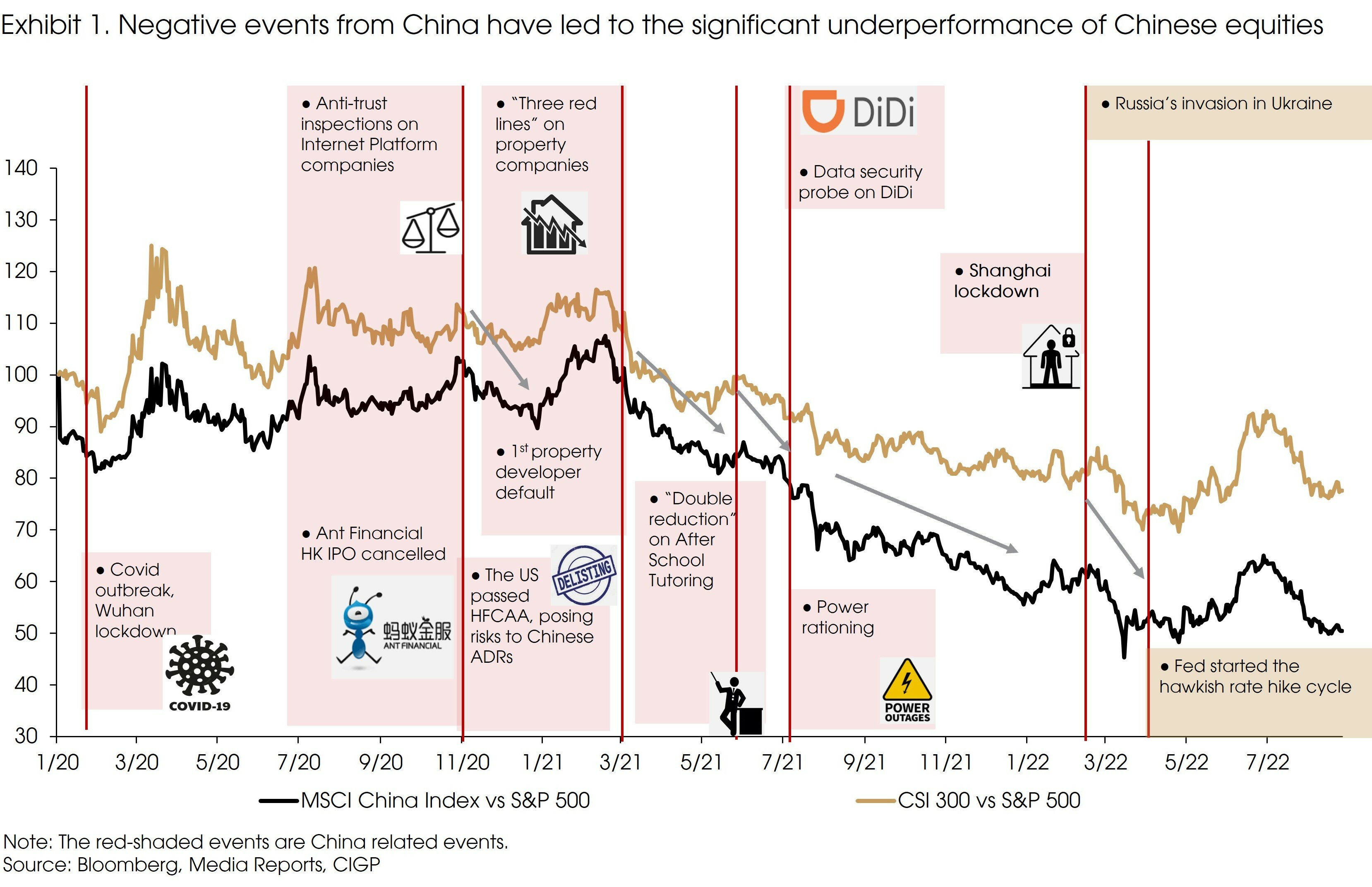

There has been a long list of events that negatively affected China’s capital markets since 2020: the COVID outbreak, the anti-monopoly moves on internet platform companies, the delisting risks of Chinese ADRs, the regulatory crackdowns on property developers, and the persistent tight restrictions on mobilities due to the “COVID-zero policy”.

Such headwinds led to significant underperformance of Chinese equities compared with other major markets, especially the US (Exhibit 1).

The underperformance resulted in lower valuations on Chinese equities. Last year’s multiple regulatory moves also indicated that regulation headwinds may have peaked. In addition, the weakened domestic growth outlook has pushed the Chinese government and central bank (the PBoC) to resume the easing cycle in 2022, in sharp contrast to the Fed.

Supported by the accommodative policy backdrop, Chinese equities were less affected by the kickoff of hawkish hikes from the Fed (from mid-March to June).

Although some market views have gradually turned positive on China, expecting the cheap valuation and supportive policy stance to lead to a mean reversion trend, significant headwinds remain.

The COVID-zero policy: The biggest risk for Chinese markets

As the world starts to “live with COVID”, China is still determined to maintain its COVID-zero policy. Such policy includes regular and frequent PCR tests among residents, the adoption of strict cross-border travel restrictions, and the imposition of region-wide lockdowns upon local outbreaks.

Although we tend to agree that the resurgence of Shanghai’s draconian lockdowns is very unlikely, we do not believe current restrictions will be significantly eased.

Such an example can be seen in Sanya, a southern city famous for tourism, which saw more than 80 thousand travelers trapped in the city, with restaurants, shopping malls, and airports closed.

We tend to treat the news of increased vaccination coverage or of the development of anti-viral pills with contained optimism. According to a University of Hong Kong study, Chinese vaccines are far less effective in protecting against the Omicron variant of the virus.

The absence of effective vaccines and the government’s determination on maintaining a low level of infections (or “COVID-zero”) prevented the implementation of an exit strategy in regards to restrictions policies, particularly when looking at the widely criticized regional lockdowns.

A prolonged COVID-zero policy would continue to undermine the recovery in the service sector, affecting the labor market and household consumption. It will also dampen the demand for business investment due to the high uncertainties to goods, labor, and service flows.

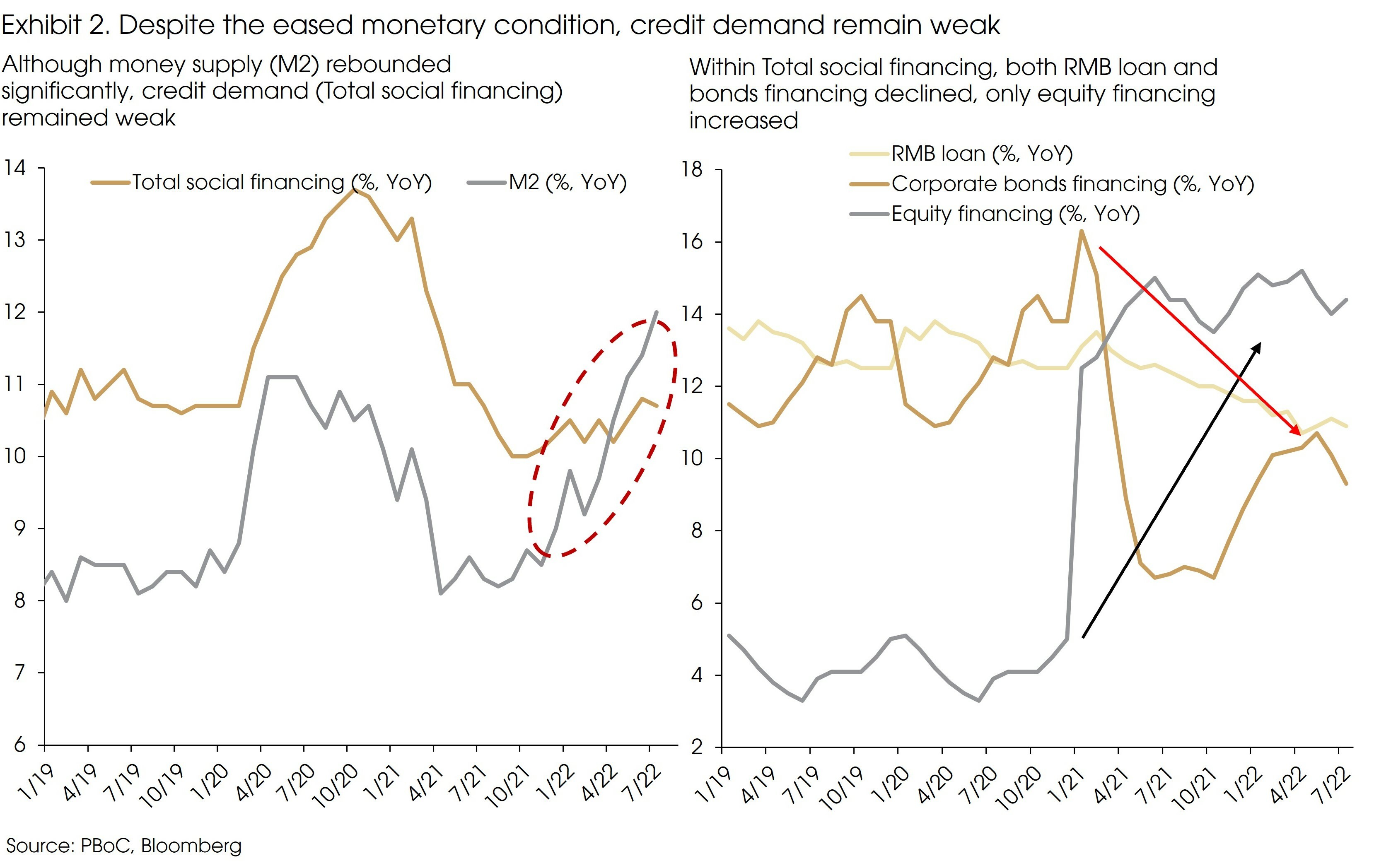

As a result, despite the continued rate cuts from the PBoC and the quick rebound of money supply (M2 growth increased from 9% at the end of 2021 to 12% in July 2022), money demand remained weak. The growth of total social financing (which measures the aggregate financing to the real economy) barely budged from 10.3% to 10.7% (Exhibit 2).

Growth of total credit demand, represented by the growth of new loans and corporate bond issuance within total social financing, significantly decelerated, reflecting the deteriorated confidence among households and corporates. Although the growth of equity financing increased, it only accounts for around 3% of total social financing and is less market-driven.

With the COVID-zero policy in place, monetary easing may continue to be ineffective to drive higher credit demand or higher economic growth.

Rising geopolitical tension: getting worse?

Speaker Pelosi’s visit to Taiwan and China’s bellicose response added to the growing list of negative headlines on China and more uncertainties to the cross-Strait tensions.

It is important to note that US politicians have been using the cross-Strait tensions from time to time, but never tried to touch the “bottom line”. In all recent comments from both the Biden’s administration and lawmakers, including Pelosi herself, the US insists that it is not changing its “one China” policy and does not support Taiwan independence.

We believe a full-out military confrontation between the US and China is unlikely. China has stayed defensive since the trade war in 2018. It has refrained from using serious retaliations against the US tariff hikes and Tech embargos, such as selling the US Treasury bonds, imposing a rare earth embargo, or sanctioning US corporations that depend heavily on Chinese markets.

Even in the recent negotiations with American regulators on Chinese ADR auditing, the Chinese authorities have shown great flexibility and willingness to comply.

Last week, the two countries finally reached an initial agreement which would allow American accounting regulators to travel to Hong Kong to inspect the audit records of Chinese companies listed in New York. The final deal still depends on some fact checks by the US. However, it is the first positive signal for the Chinese ADRs, lowering the delisting risks.

We expect the “competing without decoupling” mode between the US and China to continue. The competition will probably focus on the technology sector. The CHIPS and Science Act will restrain US companies from increasing semiconductor investment in China. According to Gartner, Intel just sold the factory in Dalian to SK Hynix due to the “pick one of two” condition within the Act.

However, non-US companies might stay neutral. Even with the proposed subsidies, the US cost of production remains higher. Samsung and SK Hynix did not change their capacity expansion plans in China. For non-US semiconductor companies, to be the foundry open to all markets with a diversified client base is still the best choice.

The housing downturn and its contagion effects

Homebuyers in China suspended mortgage repayments on pre-sold property projects in various cities due to construction delays since July. As of the end of July, there were at least 320 residential projects affected.

The real estate sector contributes 20% of China’s GDP, and approx. 40% of fiscal revenue. The property crisis in China has at least three major impacts on the economy: 1) influence on small and medium-sized banks; 2) Local Government’s fiscal revenue; and 3) the consumption demand.

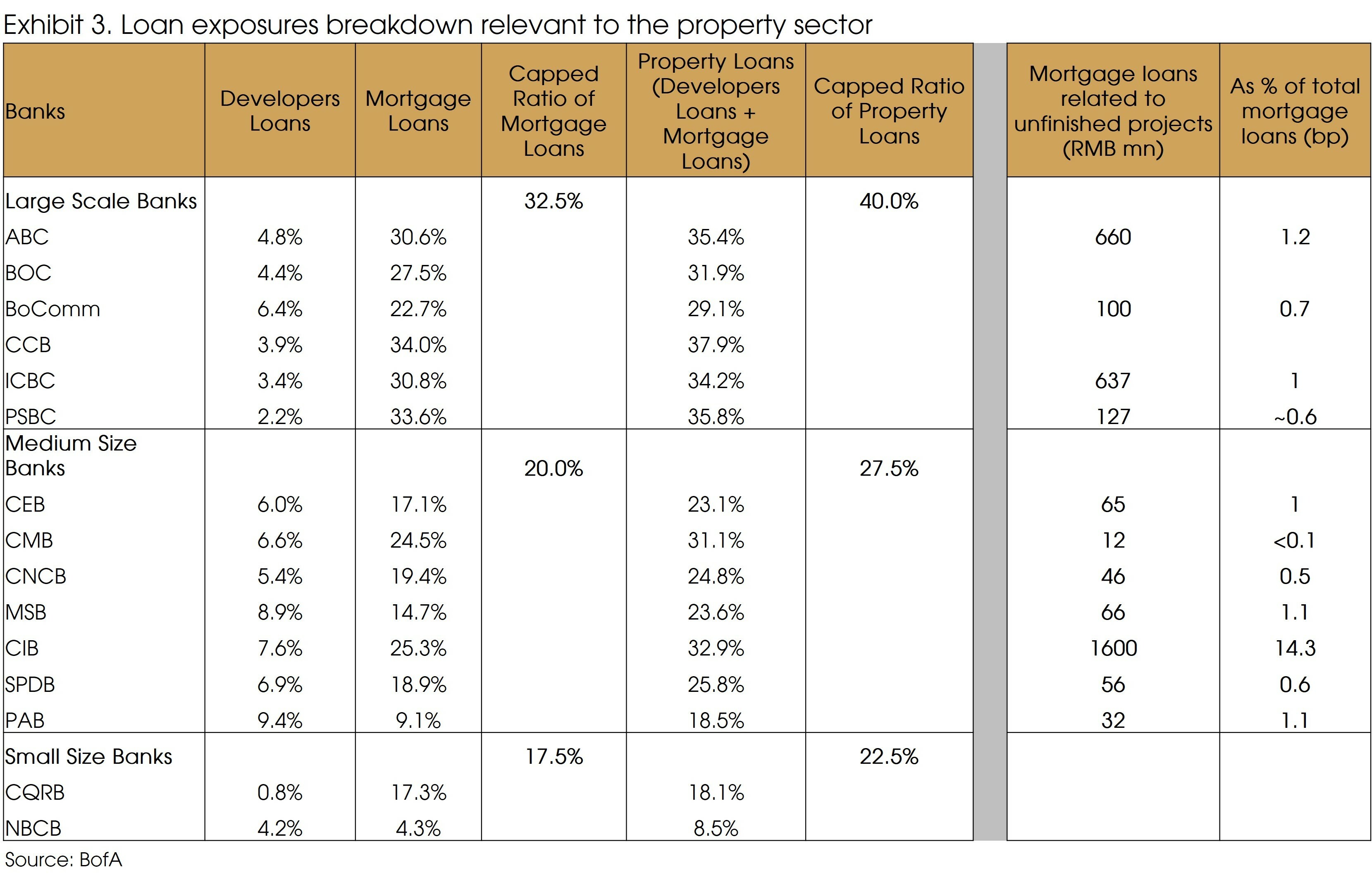

Other than the “Three Red Line” policies being rolled out in 2020, the PBoC has also issued a regulation for banks to cap their lending of property loan in order to control the leverage ratio of the industry. For large banks, the ratio of property loans to total loans is capped at 40% (including mortgages and developer loans). Smaller banks are capped at 22.5%-27.5%. The deleverage measures from the central government have reduced the overall risk exposures to the property sector significantly.

For large banks, lending came from mortgage loans account for approx. 30% of the total loans (Exhibit 3). Mortgage loans are typically high quality in China with a lower NPL ratio than developers’ loans. Large banks in general have a higher mortgage loan mix and are less exposed to private developers' loans when compared to smaller banks.

In the meantime, one should note that the size of problem loans from mortgage boycotts incident is very tiny and accounts for less than 0.01% of total mortgage loans on average. Systematic risk should therefore be contained. Large banks will be able to absorb the risk with sufficient cushion for the capital loss. Small and medium-sized banks may face a high strain, especially those with a higher developers loan mix.

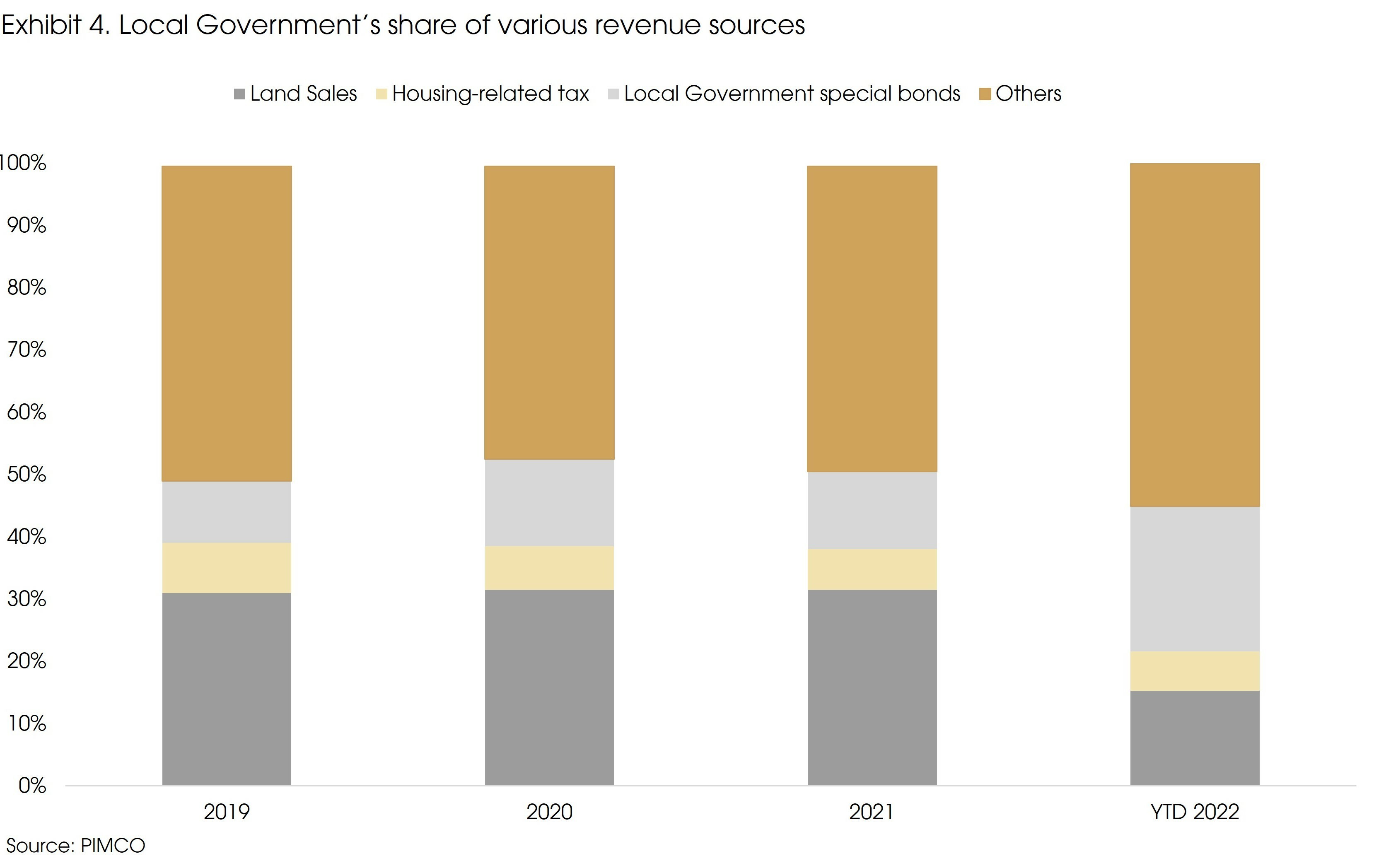

Property developers have decelerated the pace of land purchase activity to shore up liquidity since 2021. Land sales were one of the key revenue sources for local government. YTD, land sales tumbled 42% in China. They contributed at least 30% of the fiscal revenue in the past 3 years, and now only accounts for 15% of government fiscal revenue.

Over the last few weeks, sizable support has been implemented. The policy outcome is mainly to have local government or SOEs step in and provide a guarantee in onshore bond issuance to provide liquidity to developers. Local governments should thus be monitored as they could become the next risk node within this property sector issue.

Finally, China’s property sector impacts households’ balance sheets and disposable income. In terms of net wealth, China’s real estate assets account for 60% of urban households’ assets, which have exceeded RMB400 trillion as of 2020. In terms of employment, the real estate and construction industry accounts for at least 15% of the non-farm payrolls in China, which will also creates a meaningful impact to other industries such as manufacturing, mining, materials etc. In terms of household income, the real estate and construction industries account for more than 10% of wages.

A 1% decline in housing prices can possibly drag GDP by 0.3% through consumption indirectly. Therefore, the continued crackdown in the sector can create a contagion effect on household consumption demand.

That said, China’s housing market downturn is less severe than the 2008 US housing crisis in many ways: households balance sheets are much healthier, down payment ratio is elevated, and the banking system has adequate capital buffer to deal with liquidity and credit risks thanks to the reforms carried out in preceding years.

It only took three years for the US housing market and economy to recover.

Shrinking population leads to lower long-term growth

China’s population recorded near-zero growth in 2021. According to market estimations, China will see its population shrink as early as this year.

The declining population may put downward pressure on economic growth with less productivity and output (for more detailed analysis, please read our July Viewpoint: Shifting Demographics - Is the World Getting Older?)

In summary, in regard to headwinds, the housing downturn will continue to drag economic growth in the near term. However, it is not a crisis-level problem, the housing related growth concerns may gradually decline upon more targeted policy support. The “competing without decoupling” mode between the US and China should limit the downside of geopolitical tensions’ impact on the economy. The decreasing population is a key trend to watch, but it is a long-term issue with limited impact on the near-term growth outlook.

COVID-zero policy is the biggest risk to the current Chinese economy, in our view. Specifically, since we cannot see a feasible way out, at least for now.

Any potentially positive drivers?

Despite the sluggish economic outlook, we want to point out some positive factors on China’s economy and capital markets.

First, we tend to agree with the view that the Chinese market has reached a point where it is hard for negative news flows to cause further dramatic downturns.

We expect to see a more stable, or a marginally improving regulatory environment for the Internet Platform companies. The government has mentioned multiple times that it will continue to support the healthy growth of the platform economy.

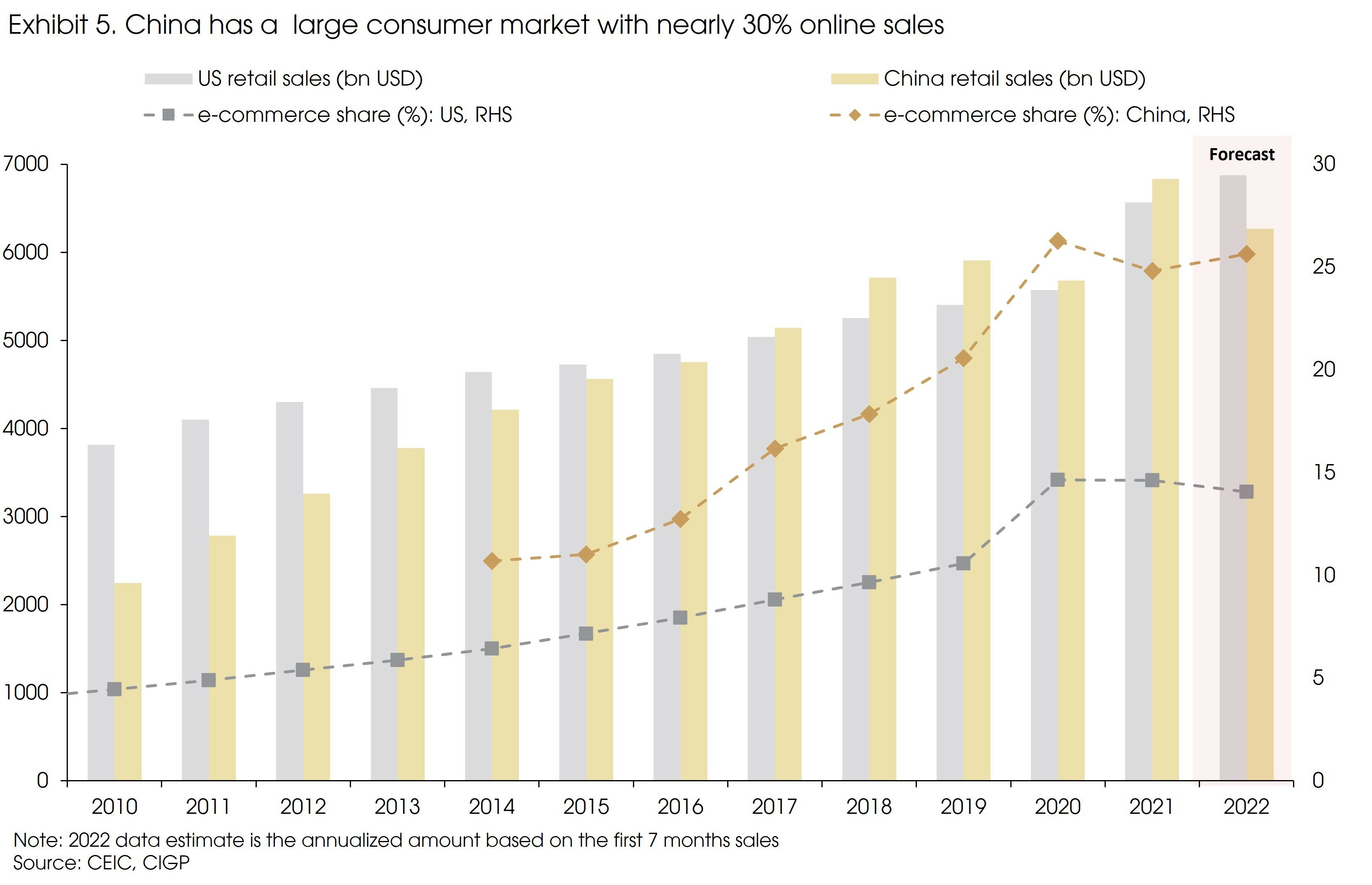

Fundamentally, China’s retail sales exceeded that of the US since 2017, becoming the largest consumer market in the world (Exhibit 5). Although the US has a higher internet penetration rate of 90% (China is at 70%), China has a much higher share of online ecommerce sales (around 26%) than the US (around 16%).

Such a sizable market with a high prevalence of online purchases will continue to provide good opportunities to internet platform companies.

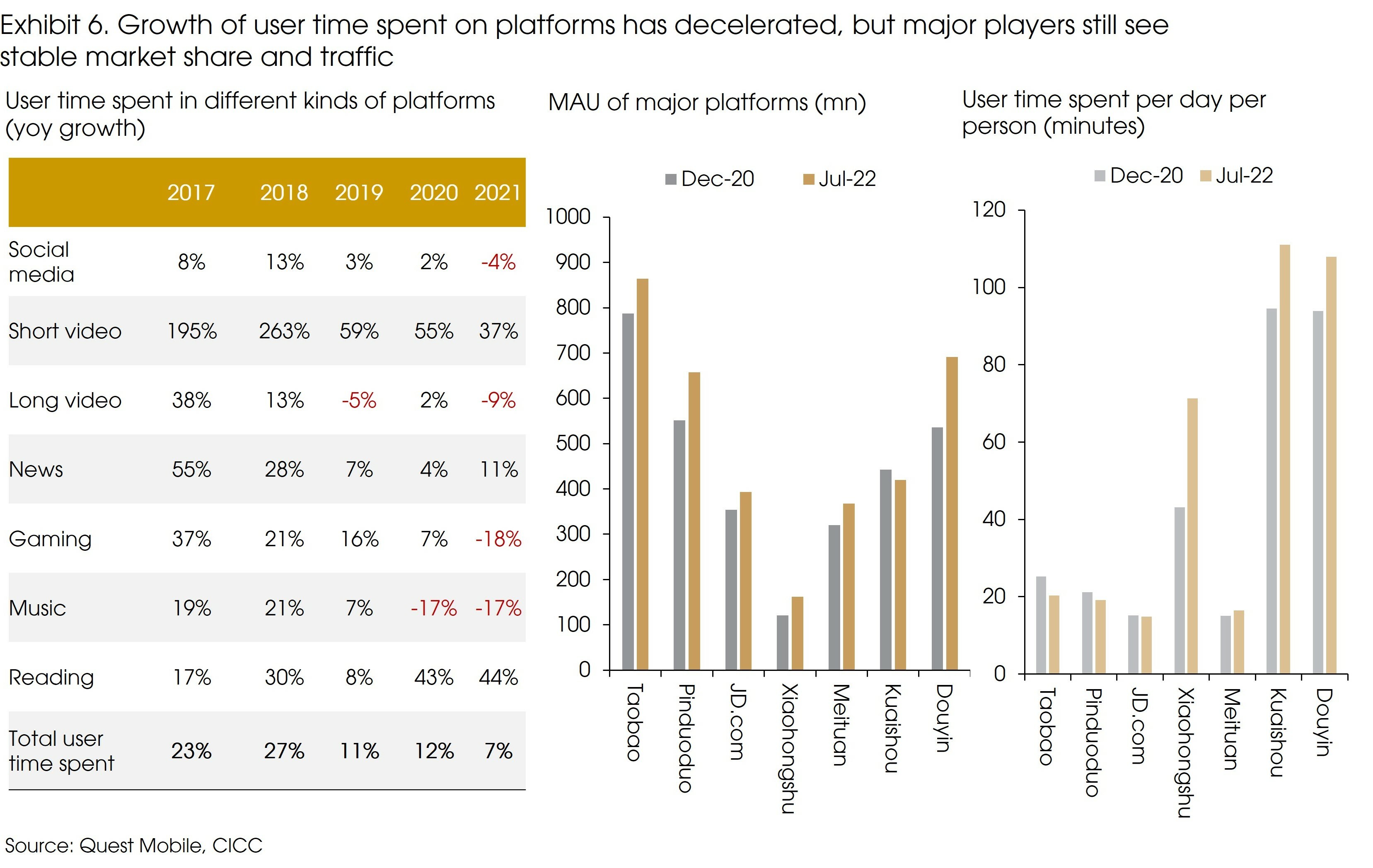

Even after the fast growth in earlier years and the “pandemic surge” in 2020, the regulatory crackdown in 2021 did not significantly affect the traffic growth on internet platforms. User time spent on the platforms increased by 7% in 2021 (Exhibit 6).

Besides, big platforms have maintained their dominance in the respective markets, despite the anti-trust moves from the government. Most of the top platform companies saw increased MAU (monthly active users) and longer user time spent, indicating high customer stickiness to the sector leaders.

However, a frequently asked question is: Despite the large scale and broad user base, what is the future growth engine for these big platform companies?

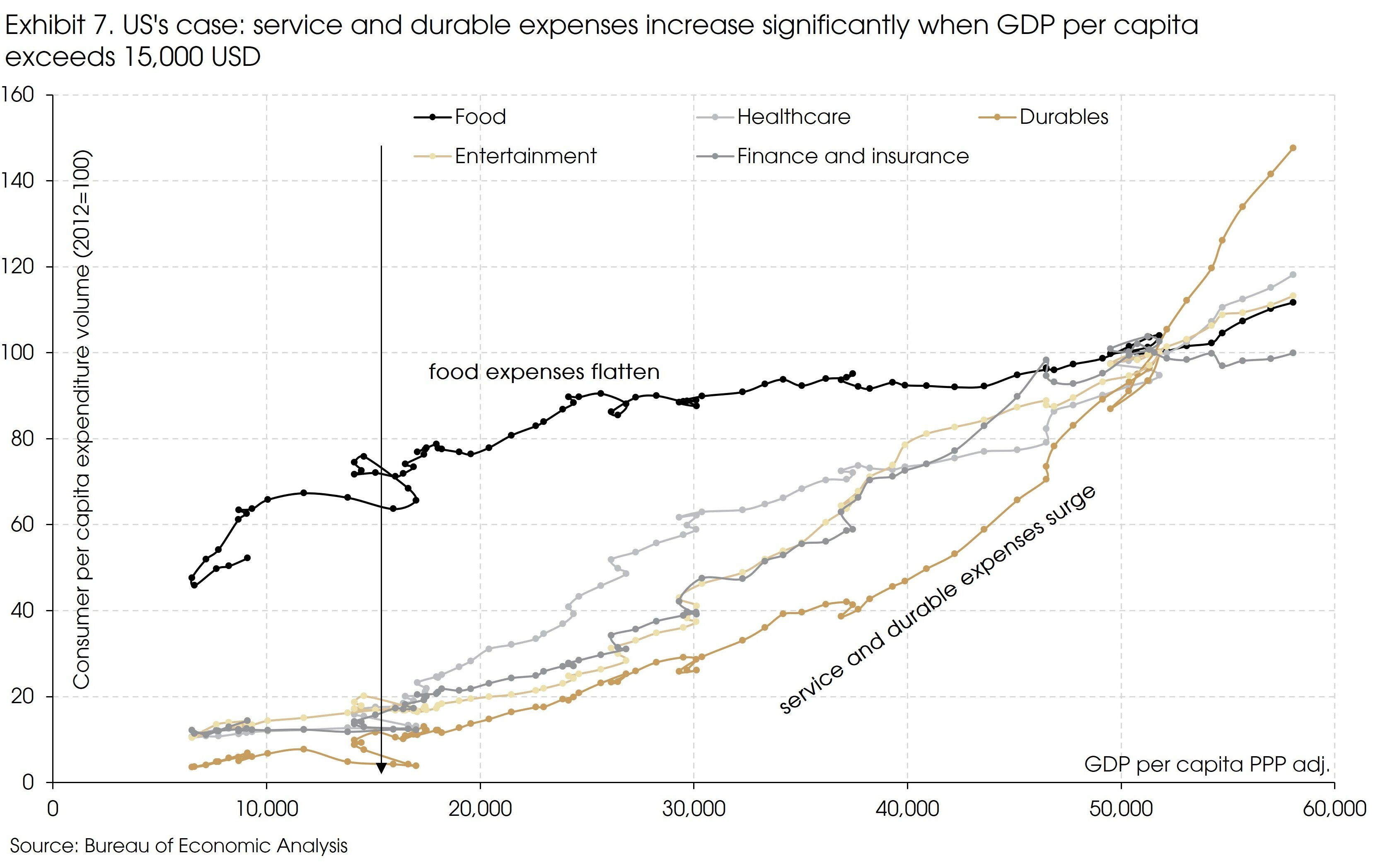

One simple answer can be the continued increase of demand from consumers, driven by income effect. Seen from the US’s experience, as individual income continues to rise, especially after the per capita GDP (PPP adjusted) exceeds USD 15,000 (China was at USD 17,602 in 2021), demand for entertainment, durable goods, and other services will increase at a much higher pace (Exhibit 7).

Such a potentially increasing demand, recent technology development e.g., AR/VR and the emergence of the Metaverse, all indicate further new growth potentials for leading platform companies.

For example, Tencent is officially launching an extended reality unit, placing its bets on the metaverse concept of visual worlds.

Platform companies are still under notable pressure for now, given weak household consumption and regulatory crackdown. However, the above also led to much lower valuations, creating compelling opportunities for long-term investors.

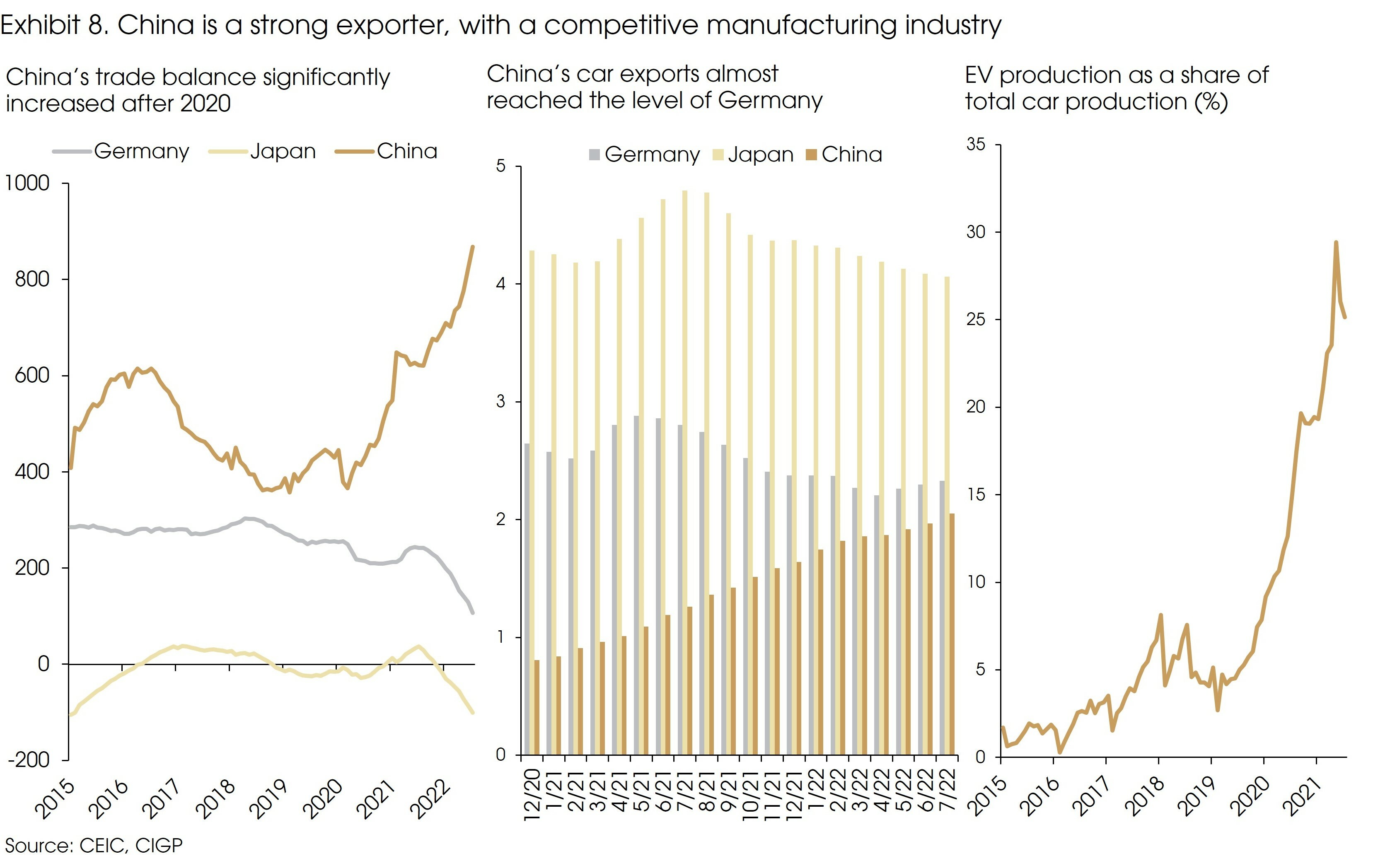

Second, China remains a competitive manufacturing country and a strong exporter. Chinese exports have continued to gain global market share in recent years, despite the trade war with the US.

China is the only major manufacturing-intensive economy that saw an increase in its trade surplus after 2020. In contrast, the external surpluses of most traditional net-exporters, e.g., Japan and Germany, have vanished due to the sharp spike in energy and commodity prices (Exhibit 8).

According to the Mercator Institute for China Studies, China’s car exports are taking off and challenging that of Germany. Most of the exported cars are electric vehicles (EVs), as the Carbon Neutrality policy boosted EV production. China could lead a changing trade pattern in the global automobile market as the car market goes electric.

Finally, the US-China policy divergence may help support the Chinese market, as the ongoing easing cycle should provide more direct liquidity support to the onshore market.

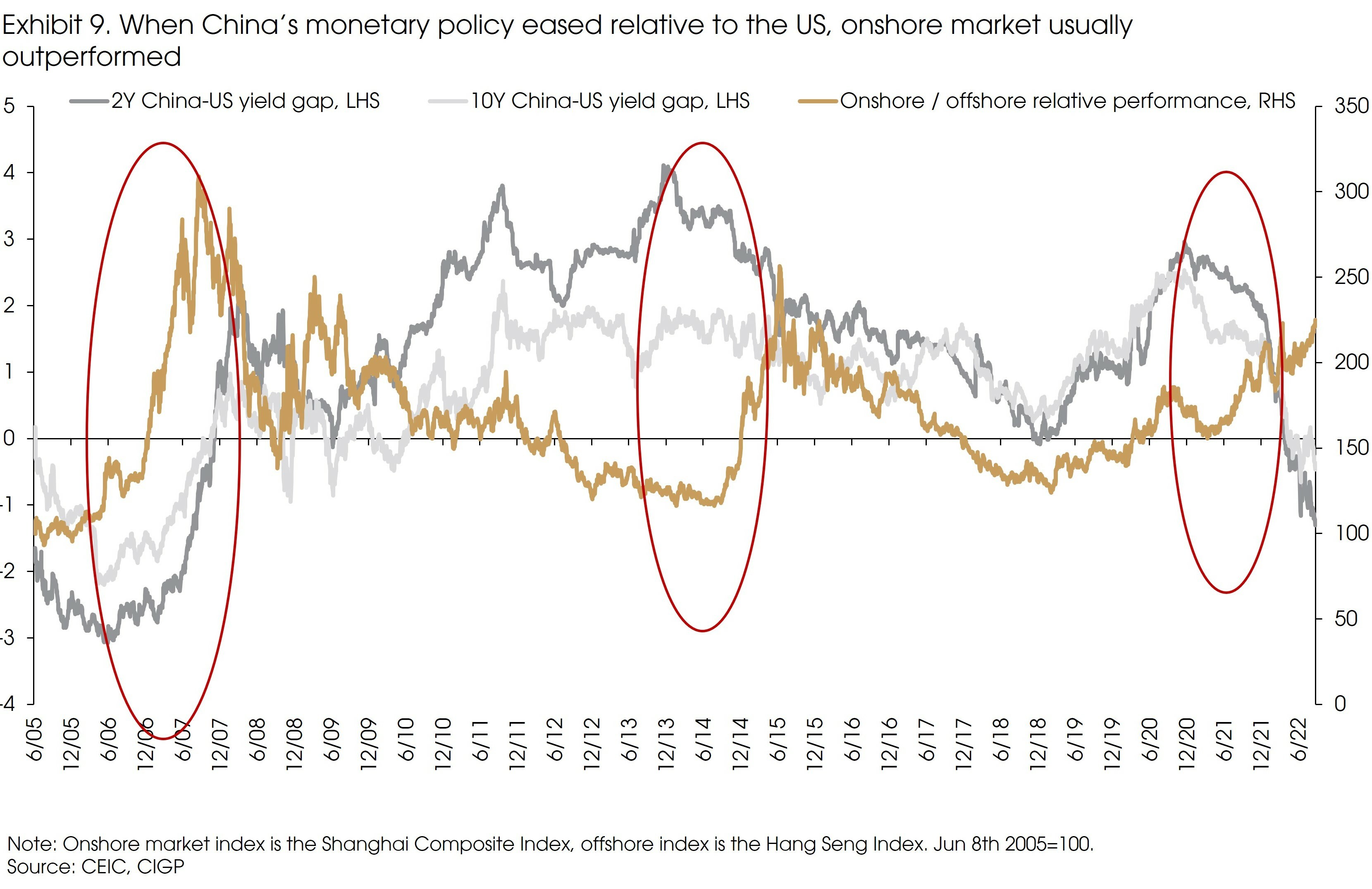

Historically, there is a pattern that when the US tightens and China eases, the onshore China market tends to outperform the offshore market (Exhibit 9). The two markets share the same fundamentals of China’s economic growth, but the offshore market liquidity is determined by the US monetary policy while the onshore liquidity is determined by China’s monetary policy.

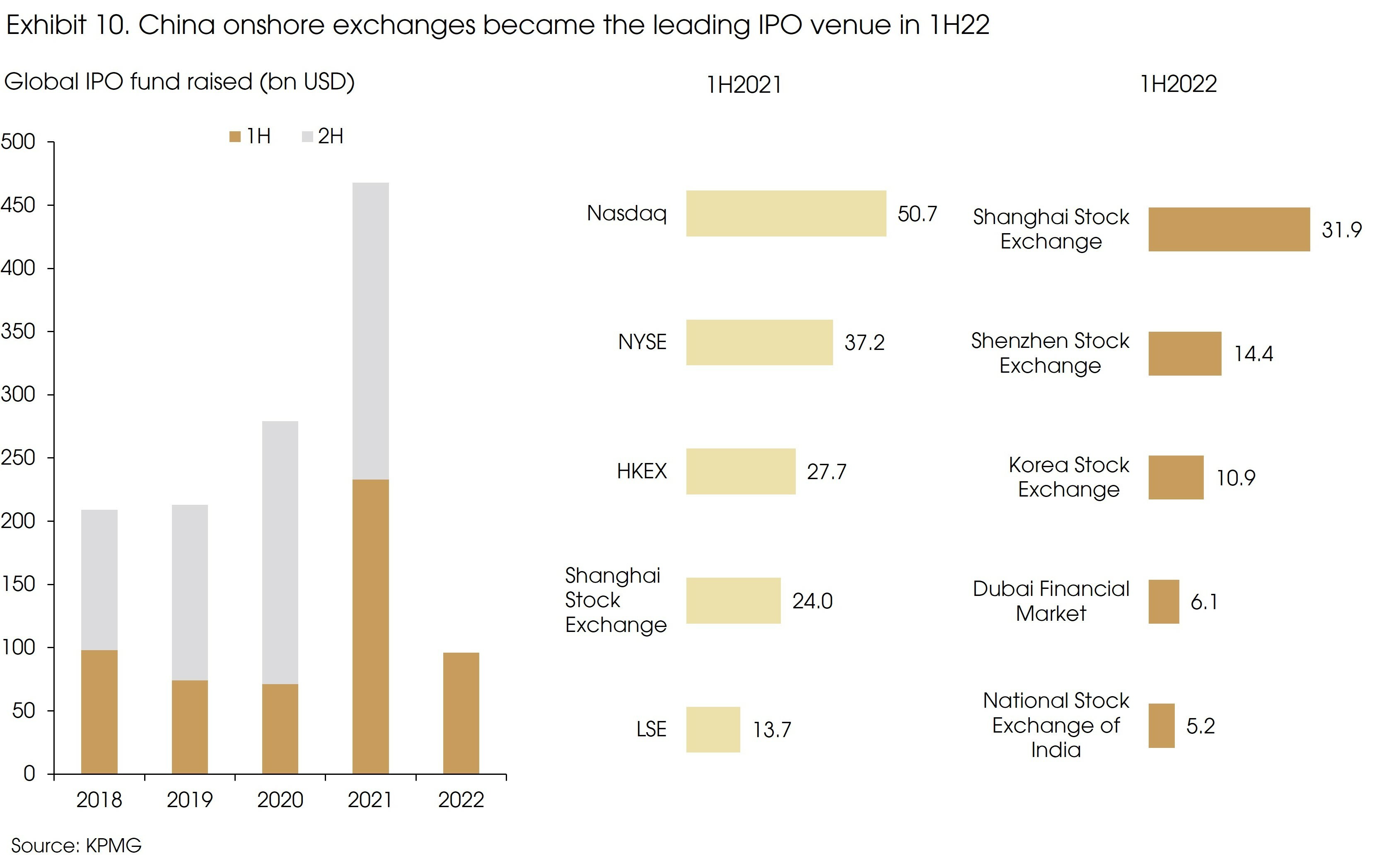

This year’s IPO fundraising numbers illustrate the difference between the onshore and offshore markets.

Global IPO market sentiment has been notably affected by geopolitical tensions, resulting in a significant decrease in fund-raising in 2022 H1 (Exhibit 10). The previously top IPO destinations, e.g., the Nasdaq, NYSE, and HKEX, all fell out of the Top 10 in 1H. Meanwhile, Shanghai and Shenzhen Stock Exchanges managed to maintain stable IPO fundraising and ranked at the top of the league table. Despite the local IPO approval system, this also suggests that the onshore market is less affected by external disruptions.

The easing policy stance and cheap valuations will provide downside protections to Chinese equities. On the other hand, risks to China’s growth remain significant, and policymakers may need to react with more aggressive measures. We remain cautiously optimistic about China’s market and would recommend staying on the sidelines until we see clearer positive catalysts.

Sources: BofA, Bloomberg, Bureau of Economic Analysis, CEIC, CICC, KPMG, PBOC, PIMCO, Quest Mobile, CIGP Estimates